In 1897, Joe Leiter was a rich, spoiled young man searching for excitement.

Levi Leiter, Joe’s dad, had made a fortune in the dry goods business and real estate in Chicago, along with mining and ranching, before retiring in 1892 and leaving Joe, who had graduated from Harvard the year before, in charge, a move he later regretted.

Wheat buying spree

In the spring of 1897 — maybe to add to his daddy’s fortune, or maybe just for the fun of it, or because bowling for $10 a pin had grown old — Joe decided to corner the wheat market. In 1897 wheat was selling for 50 cents a bushel, while corn was 19 1/2; rye, 28; oats, 14 3/4, on the Chicago Board of Trade, while it was much less farther west. In many areas corn was cheaper than coal and farmers burned it in their stoves.

Due to Leiter’s buying spree, wheat was up to 69 cents in July and 83 in August, while September futures hit $1 in late August.

Unheard of since the Civil War, “Dollar wheat” caused farmers to sell every grain of wheat they could scrape up, meanwhile praising Joe Leiter; many named their sons after him.

European farmers heard of the miracle and unrest with prices in those faraway countries spawned riots.

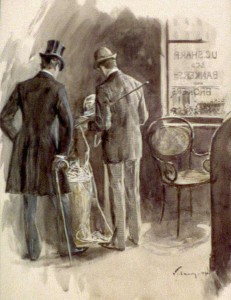

Enter Phillip Armour

Meanwhile Phillip D. Armour, born in 1832, had become rich during the Civil War by selling salt pork to the Union Army. Armour & Co. owned 6,000 refrigerator cars for shipping fresh meat by rail as well as an extensive chain of grain elevators. Much of Leiter’s wheat theoretically was stored in Armour’s elevators. Theoretical because Leiter had bought futures and contracted with Armour to store it, therefore when the grain was called for it had to be available.

In November, Leiter began exporting some 1.1 million bushels of wheat, which emptied Armour’s elevators. Leiter’s December futures would be due at the end of that month and Armour didn’t have it, leaving him what is called “short”. The only way P.D. could get out of his short position was to buy wheat or wheat futures from whoever had them, in this case Leiter, who was what is called “long,” at whatever price Joe thought the traffic would bear.

Market master

Joe stood to make a ton of money but P.D. Armour was a wily old bird. Armour not only needed to get wheat into Chicago in time to cover the Dec. 31 call date, but late enough in the season that Leiter couldn’t ship it due to lake ice, thus ensuring that P.D. got storage fees all winter.

He therefore sent his men all over the northwest to scour country elevators and farms for every last grain of wheat they could find; even some millers, chief among them C.A. Pillsbury, sold wheat they had on hand, for a premium of course, and grain was borrowed from F.H. Peavey, a large Minneapolis elevator operator. To get this wheat into his Chicago elevators, Armour chartered tugs to keep channels open through the Great Lakes ice for his grain ships, and brought in hundreds of thousands of bushels by rail.

He got more wheat than he could store and had men work night and day to build “the largest grain elevator in the world” on Goose Island in just 28 days. Although it must have cost him a fortune, by the end of December he turned over 9 million bushels of wheat to Joe Leiter who had to pay storage fees of 3/4 cent per bushel per month to Armour.

Standoff

Now Leiter could sell wheat at a high price and make money, provided buyers would pay his price. Many of the millers who had earlier sold their wheat to Armour refused to pay the price. Bakers couldn’t get flour and reduced the size of a loaf of bread and eventually used much inferior flour which, of course made bad bread.

The public blamed Leiter, who blamed the mill owners, saying that the millers could get all the good wheat they wanted — at his price, and the standoff continued through the winter. Then, in February, 1898, the battleship Maine exploded and war threatened. Wheat prices rose above a dollar on the news and Leiter’s position looked much better.

However, to maintain his monopoly, Leiter was forced to buy futures plus any wheat coming in to Chicago, stretching his finances to the limit. In a calculated move, Armour’s brokers sold a million bushels of May wheat futures and Joe had to buy it — at $1.04. Armour had hoped Leiter wouldn’t have the money, but he managed.

In March Leiter chartered 20 ships and began exporting wheat. In April, he sold 7 million bushels of July wheat, reducing his holdings by about 10 million bushels. He still was long on May wheat and owned a bunch of cash wheat however.

More finagling

At this point Joe tried for a corner on May wheat, but first visited Peavey and Pillsbury and got them to agree to not let Armour have any wheat. War on Spain was declared late in April and wheat went as high as $1.85, which was a $4 billion profit for Leiter — on paper. However, the Texas wheat harvest was early and cash grain poured into Chicago — almost 4.4 million bushels in May — and Peavey reneged on his promise and let Armour have wheat.

Again Joe’s corner was broken and wheat prices tumbled. Not only that but the 1898 crop was predicted to be 650 million bushels and it was obvious Spain’s heart wasn’t in the war, assuring an early peace.

Busted

A huge crop and a short war was not a good omen for Leiter. In mid-June Levi Leiter came out of retirement, traveled to Chicago, and took a hand in the proceedings. He and Joe met with Armour and Joe gave up. All his wheat holdings, about 15 million bushels, were to be sold, at greatly reduced prices, by P.A. Armour who got a commission on each bushel.

The fiasco was said to have cost the Leiters $10 million. Joe Leiter never bought another bushel of wheat and spent much of his time during the rest of his life in court due to lawsuits resulting from the 1897-’98 wheat deals. He was far from broke and spent a lot of time, when he wasn’t in court, at the racetrack dressed in his signature white vest and gray top hat.

Leiter’s story is another example of how speculators control the prices farmers receive for their products, a practice that continues today — just ask Marlin Clark.

STAY INFORMED. SIGN UP!

Up-to-date agriculture news in your inbox!