Tom Barton remembers what it was like living next to the largest underground coal mine in the United States: the Robena Coal Mine in Alicia, Greene County, Pennsylvania.

“It looked like a city, he said.

Every day, workers would load and unload coal on repeat, the sound of coal hitting metal and a conveyor creaking at all hours of the day. “It was loud, like a 24-hour amusement park,” Barton said.

Underground mining operations stopped in the ‘80s, and the site is now considered a brownfield site by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Tannar Barton, Tom’s son, had a different experience with his neighborhood. Growing up in the village of Alicia, after underground mining operations stopped, it was the perfect place for a kid who craved the outdoors: “I was never inside,” he said.

Tannar Barton and his friends spent hours in the woods behind their neighborhood, riding bikes, building jumps and hunting. These memories are what led Tannar to build a house next to his childhood home in 2025, so he could continue to enjoy the outdoor spaces he’s called home for decades.

But this could all change with a proposed data center set to be built in his neighborhood: “Two years ago, I got a 14-point buck, right where that data center will be,” he said.

Known as Project Hummingbird, this hyperscale data center will contain servers to support artificial intelligence. The project is set to bring thousands of jobs to the region and millions of dollars in tax revenue to the county.

While some Greene County residents see the project as an economic boon, others like the Bartons, who will live close to the data center, see it as a false promise that will cost them clean air and peace of mind.

“My whole life, I prayed when (the coal mine) shut down, I was like, thank God, no more noise. It was just quiet. Now, you can hear coyotes just yipping. You can hear anything over in them woods, anything,” Tom Barton said. “But now you’re not gonna hear nothing. Mine’s gonna go right back to the way it was.”

Project Hummingbird

The Greene County data center will be on 1,400 acres of the former Robena Coal Mine and will consist of natural gas-powered turbines to power the data center, a backup generator and a water treatment plant.

These natural gas turbines, operated by the Pittsburgh-based International Electric Power, will produce 910 megawatts of power, the equivalent of fueling almost a million homes, said David Spigelmyer, senior vice president of community and government relations for IEP.

Water is also required to cool down the natural gas turbines and the AI data servers. According to Spigelmyer, the gas turbines will use 8 to 9 million gallons of water a day from the Mongonghela River. In total — data servers included — the project may consist of up to 17 million gallons of water a day.

After the water is used, it will be released back into the environment as steam. As of the deadline for this story, IEP has not found an investor to develop and operate the data center portion of the project.

The project is expected to bring 1,500 construction jobs each year over six years to build the plant, and 150-200 permanent data center jobs.

There will also be 40-50 jobs necessary to operate the on-site gas turbines; IEP is working with career and technical schools to train workers for these turbines, says Spigelmyer.

The project will bring much-needed tax revenue to the region, too, according to Jared Edgreen, chairman of the Greene County Board of Commissioners.

“For so many years, this county thrived on coal tax revenue, and we’ve seen that go down (along) with the jobs as well,” Edgreen said. “(The data center) is going to improve our communities. It’s going to invest back into our schools, the township down there, and these are going to be family-sustaining jobs for our residents.”

Because the data center will be on a brownfield site, the company will have to follow Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection and U.S. EPA guidelines to reclaim the site, a huge bonus, Edgreen said, as the county has wanted to clean up the former coal mine for decades.

According to Edgreen, the county gets some brownfield funding, but the site would take millions of dollars to reclaim — money the county doesn’t get from the state or federal government.

Meanwhile, the site still contains “copious amounts of coal refuse (coal waste containing toxic heavy metals), gob piles and retention ponds,” said Edgreen. “And it’s so close to the Mon River that because of that coal refuse, a lot of that is leaching into the river.”

An energy-rich county

Large-scale commercial mines wouldn’t start until 1902 with the opening of the Dilworth Mine.

The Robena Coal Mine opened in 1944 by the H.C. Frick Coke Company to provide coal and coke to the U.S. steel manufacturing industry in Pittsburgh and surrounding areas. At one point, it was said to be the largest “mechanized” coal mine in the U.S.

Deep mining operations at Robena stopped in 1983, while preparation plant operations — crushing, screening, cleaning and sorting raw coal to remove impurities — continued until 2007.

The Robena Coal Mine peak and closure represent a similar trend across Greene County and the region. In 1986, the Nemacolin mine, another high-producing mine in the county, closed.

According to a Kleinman Center for Energy Policy report, coal mine closures are a result of low natural gas prices, increased environmental regulations and a lack of electricity demand for coal.

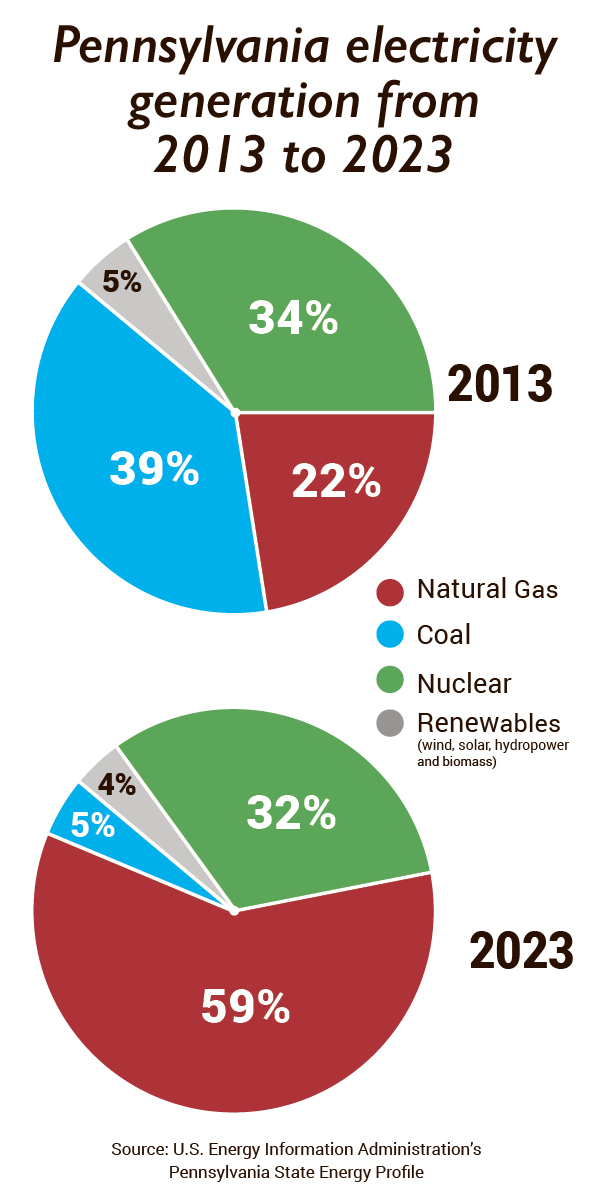

In 2013, coal supplied 39% of Pennsylvania’s power; a decade later, coal would only produce 5% of energy in the state.

When the coal mines started to close, so too did the steel mills that relied on coal production to operate, leading to an economic downturn in the region that it didn’t recover from until shale gas development began in the 2000s.

The first unconventional oil and gas well drilled in the state was in neighboring Washington County in 2004; unconventional natural gas drilling expanded into Greene County in 2006.

While the natural gas industry has helped support the county economically after the fallout of coal and steel, residents say Greene County is still struggling.

An empty Waynesburg

Joseph and Rebecca Martinak drive through the streets of Waynesburg, pointing out businesses and infrastructure that weren’t there two decades ago.

“The whole time I was a kid, we had to wait for the train when we were on our way to school. An ambulance could not get to a wreck because it couldn’t get through,” said Rebecca Martinak, a longtime Waynesburg resident, talking about the lack of infrastructure in Greene County before fracking.

According to the Martinaks, in the early ‘00s, Pittsburgh-based natural gas company EQT built a bridge above the railroad tracks to haul its fracking wastewater, something which has also benefited the community.

“Bam, and then the roads started getting improved, money started coming in,” says Joseph Martinak, as he passes the EQT REC Center that the company also helped build.

Further up the hill, the vehicle travels past concrete companies, trucking businesses that haul brine waste and a car dealership with a parking lot full of trucks for sale — EQT buys a lot of these trucks, according to Joseph Martinak.

These businesses, which supply many of the oil and gas companies in the area, were formed or boosted as a result of the modern-day unconventional oil and gas industry, said the Martinaks.

But while these businesses thrive, other local businesses continue to decline: empty storefronts line the sidewalks in downtown Waynesburg that once housed a grocery store, a women’s clothing shop, a shoe store and a theater.

Now, strolling through downtown only makes the Martinaks nostalgic for the past. “Friday night was busy, people got paid. You went up, you parked along the street, you walked back and forth to the stores, you sat on the courthouse wall and talked to people,” Rebecca Martinak said.

“People didn’t worry about finding a job,” she said. This all changed in the early ‘80s when the coal mines and steel mills began closing.

As fewer jobs became available, more and more residents left Greene County, the Martinaks included.

“I would have been a steel mill hunky. Without a doubt, I would’ve followed my dad, who followed his dad, who followed his dad into the mill,” said Joseph Martinak. But after graduating high school, there were no steel jobs left, which led him to join the military.

Rebecca Martinak moved to Maryland, but wouldn’t be gone for long. She moved back to Waynesburg in 1989, wanting her children to be raised at home.

But when the kids were all grown up, they ended up moving away anyway, unable to find a job. Rebecca Martinak’s sisters have also since moved away.

The population in the county has been steadily declining for decades. In 1950, 45,251 people lived in Greene County. Today, 35,954 residents live in Greene County

Despite the impact the Marcellus Shale boom had in Greene County, Waynesburg and other small communities are still struggling. That’s why the Martinaks are pinning their hopes on Project Hummingbird.

Greene County, Pennsylvania population 1950s-present day

The Martinaks, who have been attending public meetings about the Greene County data center, say the declining population and economy are due to the lack of jobs in the area, in addition to the opioid crisis, which has left many in the county unable to hold a job.

Studies have found high rates of opioid prescriptions and overdoses in communities that housed the underground coal mining industry.

The Martinaks believe the data center could be a catalyst for a growing population and thriving county again. “It might only be 250 jobs, it might be 100 jobs, but it’s jobs. But not only that, but it also brings a tax base,” said Joseph Martinak.

“We would like to see kids grow up here, be successful here, have jobs here, and be able to make a life,” said Rebecca Martinak.

But for those who will live close to the data center, it will be another noisy neighbor operating at their doorstep.

A close-knit community

Sitting around the Bartons’ kitchen table, Alicia residents reminisce over the old days, when coal was king. The village was founded as a company town for the coal mine, with houses built for the workers — some of which are still standing.

There are currently 28 houses occupied by seven families and four people in the community, Kimberly Barton said. The isolated community, with only one road leading in or out, has become a haven for wildlife and has led to neighbors forming close bonds over the years.

Tannar Barton and his neighborhood friends spent so much time outside together that their parents built a quad trail in the woods, connecting their houses — an attempt to keep them safe and off the road.

One neighbor, Michelle Balencheck, got married in the Barton’s backyard, a testament to how close the community is: “We’re all family here,” Balencheck said.

These memories are what led Tannar Barton and his girlfriend, Shayla Keener, to move back to Alicia with her five-year-old daughter.

“The thing that I love the most about (Alicia) is I’m related to most of the people. It’s a unique town to us, it’s a family town,” said Kimberly Barton. That’s what prompted her to give a portion of her land to her son Tannar Barton, “to continue the tradition of being a family town.”

But the proposed data center has many residents questioning their future in Alicia; specifically, they are concerned about the close proximity of the natural-gas powered turbines to their houses.

Emissions

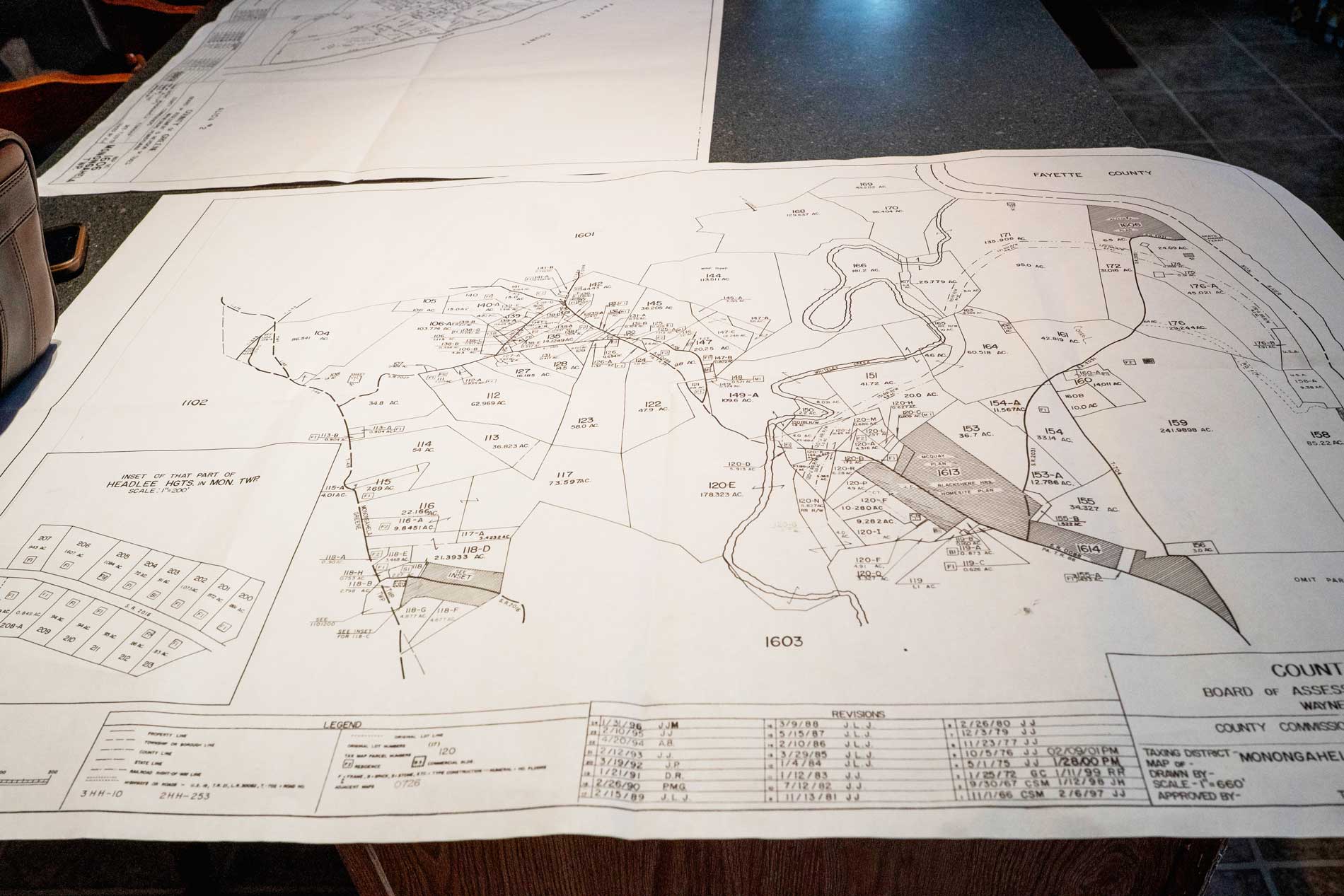

Standing on the side of her house, Kimberly Barton points out a blue building visible through the trees that surround her property. “That’s where the gas turbines will be,” she says, a few hundred feet from her house and dozens of others in the small riverside community of Alicia.

Alicia is already in an environmental justice area, a community facing a disproportionate amount of environmental hazards, as stated by the EPA.

According to the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection, only 6% of communities in the United States face higher environmental risks than Alicia.

With the gas turbines, Kimberly Barton is particularly concerned about nitrogen oxide gases, volatile organic compound emissions and particulate matter that will be released into the atmosphere.

“Is it going to affect the quality of our soil for growing? We have chickens. Is it going to affect any of the outdoor animals and things like that, as well as the health impacts for the community?” said Kimberly Barton.

Already, she has bought air quality monitors and soil quality tests to get a baseline reading before the data center comes in.

According to the U.S. Congress website, natural-gas facilities produce pollutants like methane, volatile organic compounds (VOCs), nitrogen oxides and sulfur dioxide.

Long-term exposure to NOx (nitrogen oxides) gases can lead to the development of asthma and respiratory infections, states the EPA, as well as cause acid rain in the environment and alter the growth and survival of plants.

“For (a few) viable, long-term jobs, you have 28 houses of people that are being affected by the environmental impacts of it,” Kimberly Barton said. “So for me, being an Alicia resident, the benefits do not outweigh the risks.”

For Tom Barton, who has lived in Alicia since birth, the gas turbines going in beside their house are not much different from living next to the coal mine. Every year, large coal piles would be blown by strong winds, coating the residents below and their houses in coal dust.

“The coal pile here would be as big as the entire town,” he said. “So now, you’re going to put power plants right beside us. And where’s that wind gonna go? It’s gonna lay it right on top of you again.”

“The worst thing is it’s right beside us. It wouldn’t be so bad if it was down the river somewhere,” he added.

The Bartons aren’t the only ones concerned. Balencheck grew up in Alicia and has since moved away, but her mother and 7-year-old nephew still live there.

She’s concerned about their health, as well as the noise from the data center: “(My nephew) has real bad sensory issues, and if it’s really loud, he won’t go outside,” Balencheck said.

Others are worried the noise from the data center will drive away wildlife, which is the reason why many of the residents enjoy living in Alicia.

According to IEP, the data center will be 55 decibels from the fence line of the data center, the equivalent of a normal speaking voice, and will operate 24/7. The noise will be nothing compared to the former coal mine, says Greene County Commissioner Edgreen.

“I talked to a lot of residents down there, too, in the town hall, and their generational residents. They lived next to the largest coal mine in the world; that had to have been immensely loud. This is not going to be that,” said Edgreen.

A vote

On Dec. 17, the Greene County Planning Commission approved phase one of Project Hummingbird, which will consist of site remediation — cleaning up a portion of the coal waste. If approved, phase two will kick off preparations for site infrastructure, including the water treatment plant and power plant.

The commission approved phase one because the company met all legal requirements, said Julie Gatrell, chairman of the Greene County Planning Commission. However, she emphasizes the board has some concerns about the project.

IEP will have to acquire multiple permits and hold public hearings, as the data center is going on a brownfield site, and it must be properly cleaned before being redeveloped.

Meanwhile, Alicia residents are considering their options as the data center plans move ahead. According to Kimberly Barton, IEP plans to meet with the Alicia residents to hear and address their concerns.

Despite this, most homeowners in Alicia are hoping the company will buy out the community if the data center comes in. But leaving Alicia means leaving behind family.

“I really never wanted to leave,” said Tannar Barton. “I don’t want to move anywhere else, truly. But, if push comes to shove, and we do have to go that route, then we’ll go somewhere else in the countryside, away from everything again.”

“The only thing with relocating is the neighbors,” Keener added. “You’re not going to be able to bring all your neighbors.”

(Liz Partsch can be reached at epartsch@farmanddairy.com or 330-337-3419.)

Beautiful story,very inTeresting, yes it really must have been polluted be oN belief with 6 generations retiring from the stee! Mills but they retired and pollution come with manufacturing not as bad as it was years ago I know I worked in the steel mill at Mansfield Ohio 60 year ago, everybody wants it for stay the same,but it’s not going to happen, that’s progress.

Reading this article, it’s clear that the proposal to build a massive data center on the old Robena Coal Mine site in Greene County is stirring deep and understandable emotions on both sides: some see it as a much‑needed economic opportunity that could bring jobs and tax revenue to a struggling region, while longtime residents fear it could disrupt the quiet, close‑knit community they’ve cherished for generations and potentially harm the environment and quality of life with noise, emissions, and industrial infrastructure right in their backyard.

Greene County residents’ debate over the proposal to build a data center on the former coal mine highlights important concerns about environmental impact, economic benefits, and community priorities. While a data center could bring jobs and modern infrastructure, residents are rightly cautious about potential environmental risks, such as land use changes and ecological disruption. It’s crucial that the decision-making process involves thorough community input, environmental assessments, and clear plans to mitigate any negative effects. Finding a balanced approach that benefits the community while preserving its natural and historical resources should be the goal.

The entire site has been posted with No Trespassing & No Hunting signs since the mining stopped. So, lamenting the loss of your deer stand in the middle in the property is a heart-tugging but quite BS storyline.