The country is about to embark on a feat comparable to the “urgency and ambition of the Manhattan Project in World War II.”

That’s according to a series of executive orders from the Trump administration that declared a national emergency last year over an “inadequate” supply of energy — something both Republicans and Democrats like Pennsylvania Gov. Josh Shapiro agree on.

Through a January 2025 executive order, Trump called for expediting permits for energy infrastructure by modifying environmental regulations.

“Without immediate remedy, this situation will dramatically deteriorate in the near future due to a high demand for energy and natural resources to power the next generation of technology,” the executive order reads.

This next-generation technology is known as artificial intelligence, and it’s right at the doorstep of Ohio, Pennsylvania and West Virginia.

Artificial intelligence, known as AI, has the potential to transform everyday life.

But with this transformative technology comes data centers: huge buildings containing AI computing servers that store information. These data centers can require their own power supply, thousands (sometimes millions) of gallons of water and hundreds of acres of land — and they are coming to a community near you.

What is a data center and AI?

Artificial intelligence is technology trained to perform human tasks, using information from data sets to solve problems, plan and make decisions.

Advancing AI is a key part of the Trump administration’s agenda; so far, the administration has released multiple executive orders and an action plan to accelerate AI data center development and lead the international AI race.

One executive order directs the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to modify the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, the Toxic Substances Control Act and other related laws to expedite AI data center permits on federal and non-federal lands like brownfield and superfund sites — contaminated land.

Another executive order pushes for the development of more U.S.-manufactured AI hardware, models, servers, etc.

This is part of the administration’s “AI race” against China and other foreign countries; China is also rapidly developing AI hardware and models.

The U.S. Department of Defense officials stated earlier this year that AI plays a crucial part in safeguarding the military against espionage and data breaches.

But, in order to expand this “next generation technology,” more hyperscale data centers — that store AI software — will need to be built across the country

Traditional data centers have existed for decades to store and distribute data used to power the internet. While the internet and the “cloud” are often seen as an invisible force that exists in people’s homes, the equipment to make it happen must be physically housed somewhere. These data centers typically support website hosting, cloud storage and more.

AI data centers, however, are newer. Also known as hyperscale data centers, these facilities require more land, water and energy to operate than traditional data centers. That’s because they are designed to process larger volumes of data, run learning models and support AI-driven tasks.

AI for good

AI is considered a necessary investment to some people, as it can improve society by automating tedious tasks, enhancing decision-making with data insights, reducing human error and solving complex problems.

That’s why many land-grant universities like Penn State and Ohio State University are investing in the technology. Already, researchers are evaluating AI’s potential to improve animal health and produce higher crop yields.

In December, Penn State, the University of Kentucky and the University of Delaware received a $1 million grant to develop an AI system that will detect bovine respiratory disease — the leading cause of death for dairy calves after they become accustomed to food other than their mother’s milk, according to PSU.

Known as CalfHealth, it will monitor several data types, including behavior data (collected through low-cost sensors that calves will wear), feeding behavior (through robotic feeders) and breathing patterns using a WiFi-based sensing system.

AI will use this data to determine illnesses based on changes in behavior and breathing.

Penn State is also developing an automated robotic weed management system that will be used to effectively control weeds in apple orchards.

Researchers are developing an AI system that can accurately find, interpret and estimate the density of weeds in apple orchards using a side-view camera. Once the system identifies the weed, it applies a small amount of herbicide to manage the weeds.

OSU is paving the way for AI use in agriculture, too. At its annual 2025 Farm Science Review, Laura Lindsey, soybean and small grains specialist with OSU’s College of Food, Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, tested Agroptimizer, a new AI-powered decision-support tool that can predict when planting soybeans will produce the highest yield.

OSU Extension staff also discussed new AI tools that can help farmers make field-based decisions on planting and disease management.

An energy appetite

While AI can be beneficial, other academics and researchers warn that AI data centers will increase electricity costs for consumers due to the large amounts of energy and water required to operate them.

In 2023, data centers consumed roughly 4% of the U.S.’s total electricity consumption, according to an Electric Power Research Institute study. This amount is expected to rise anywhere from 6.7% to 12% of the total U.S. electricity supply by 2028.

New hyperscale data centers are being built to use 100 to 1,000 megawatts each, the equivalent energy usage of 80,000 to 800,000 homes.

In and around western Pennsylvania, data center growth could increase electricity prices up to 25% by 2030, according to the recent Open Energy Outlook Initiative, a collaboration between Carnegie Mellon University and North Carolina State University that modeled energy and emissions implications for expected data center growth.

“It’s important (for everyone) to understand that the electric power system is maintained and invested in by everybody who uses it,” said Mike Blackhurst, executive director of the Open Energy Outlook Initiative and professor at CMU.

Blackhurst explains that when a large user of electricity connects to the power grid, everyone has to ensure there’s enough generation and transmission to meet those demands.

“Customers who struggle with paying their utility bills don’t have the resources they used to have to pay them, and we’re asking the everyday person to support these AI companies’ growing power demands,” Blackhurst said. “It just seems very backwards to me in so many ways.”

Some Ohio residents are already seeing an increase in electricity bills.

The state currently ranks fifth in the country for the most data centers online, according to datacentermap.com. Specifically, central Ohio leads the state for hyperscale data centers with over 100, owned by big tech companies like Google and Meta.

But these tech giants are costing residents higher electric bills. In summer 2025, many Ohio AEP customers saw an increase of $27 a month on the electricity generation portion of their bills, “because of an imbalance between the supply of electricity being generated and the demand for it,” reports AEP Ohio.

Millions of gallons

Water also plays an important role in data centers. Traditional data centers use air conditioning to cool down servers, while hyperscale data centers with AI servers require water cooling.

“(Data centers) have gotten so large that the air cooling costs would be too great for (companies) to meet their profit goals,” said Andy Yencha, a renewable and natural resource extension educator at Penn State University.

Water can remove more heat than air cooling can, Yencha adds. But, depending on the size of the data center, thousands to millions of gallons of water are required.

A 100 megawatt data center can consume the same amount of water as 2,600 households, as reported by an International Energy Agency study. This water often comes from local waterways or local water utilities.

Both the AI servers and these water cooling systems require energy to operate; according to an Electric Power Research Institute study, IT equipment accounts for 40% to 50% of energy consumption in a data center and cooling systems account for 30% to 40%.

The power plants used to power these data centers will also need water for cooling, Yencha said, which adds to the overall water usage of data centers.

As companies look to put data centers in the region, Yencha hopes they are taking into consideration unpredictable weather events like severe drought conditions. In the last two years, portions of Ohio, Pennsylvania and West Virginia have experienced severe drought conditions in late summer.

“What happens if (a river) goes into drought and is cut by half or three-quarters of its normal flow? What is the plan, then, for the data center? Because these data centers can’t cut back once they’re built,” Yencha said.

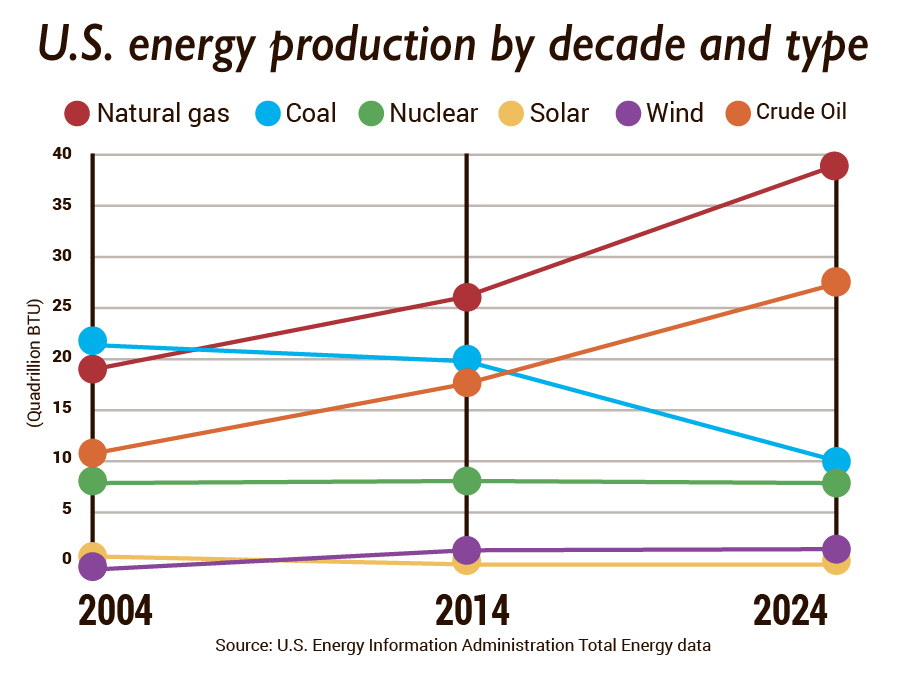

To meet AI’s large energy and water demands, the U.S. will have to increase energy production across the country.

More power plants

According to the Trump administration, the current “inadequate” energy supply has led to high electricity prices, and a lack of energy is a national security threat. This is where Appalachia fits into the picture.

The central Appalachian region of Pennsylvania, Ohio and West Virginia is poised as a prime spot for AI data centers due to its natural resources: energy and water.

Natural gas will likely power most hyperscale (AI) data centers in the tri-state area, along with nuclear power, as pushed by the Trump administration’s national emergency executive order.

Electricity consumption is expected to double by 2030 to meet the energy demands of AI, according to a July 2025 report by Oklahoma State University.

“This level of energy use would exceed the electricity consumption of entire industrial sectors or small-to-mid-sized nations, putting substantial pressure on existing power generation and grid infrastructure,” states the report.

“This alone could require dozens of new gas-fired plants, equivalent to powering 20–30 million additional homes.”

This is already happening. In Pennsylvania, a former coal-fired power plant, the Homer City Generating Station in Indiana County, will be transformed into a natural gas power plant to support a nearby AI data center.

Three Mile Island, the site of the worst nuclear accident in the country, located in Middletown, Pennsylvania, will also reopen to produce nuclear energy to power Microsoft’s AI data centers.

In November, the Ohio Power Siting Board approved a behind-the-meter natural gas-fired power plant to power a data center in Licking County, Ohio.

More emissions

According to CMU’s Blackhurst, communities that house data centers will see an increase in greenhouse gas emissions and health risks as more power plants come online. The CMU initiative predicts emissions will increase by 30% by 2030 as more data centers come online.

In particular, Ohio, Pennsylvania and West Virginia will see an “overwhelming majority of that increase in emissions,” Blackhurst said, due to more energy extraction in the tri-state area, as well as power plants and diesel backup generators for data centers.

As many companies turn to existing coal-fired and natural gas power plants to fuel data centers, he adds that there could be “public health implications from continuing to operate those older, less efficient generators.”

“I totally understand that there are opportunities for labor in these legacy industries, but there’s also some risks to public health from emissions from burning fossil fuels,” Blackhurst said.

The Trump administration projects hundreds of thousands of jobs to come from data center development across the country, which would include temporary construction jobs and permanent jobs.

Blackhurst says there would be some job benefits for communities, particularly those with old coal-fired and natural gas power plants, but that they will be short-lived.

“I do think that (data centers) put us at risk in many ways. It puts us at risk from an affordability perspective. It puts us at risk from a public health perspective. It puts us at risk from an environmental perspective,” Blackhurst said.

“It seems to just really favor the already winners in society, which are those who have hundreds of billions of dollars to build data centers.”

(Liz Partsch can be reached at epartsch@farmanddairy.com or 330-337-3419.)