YouTube has a video titled “Catching Ultra RARE Blue Pike Walleye from a Secret Lake!”

Outdoor News published an article in 2023 with the headline “De-extincting the Great Lakes blue pike may be worth looking at.”

The Division of Wildlife offices in Sandusky and Fairport Harbor occasionally get calls from anglers claiming they’ve caught one. But the blue pike is the Loch Ness monster of Lake Erie. People claim to have seen it, even caught it. But it’s a matter of longing to revive a legend, not a matter of fact.

“It has captured a lot of people’s imaginations,” said Travis Hartman, Lake Erie Fisheries Program Administrator for the Ohio Division of Wildlife.

However, the 1975 declaration of the blue pike’s extinction still stands, he said.

Surprising disappearance

Some species are said to be “extirpated,” meaning they’ve disappeared from a particular area or state. Like the passenger pigeon, “extinct” means they’ve disappeared from the planet.

And that’s especially surprising for a fish that was commercially harvested in Lake Erie for more than 100 years. Prized for its tenderness and sweet taste, it was considered even more desirable than today’s sought-after species, the walleye and perch.

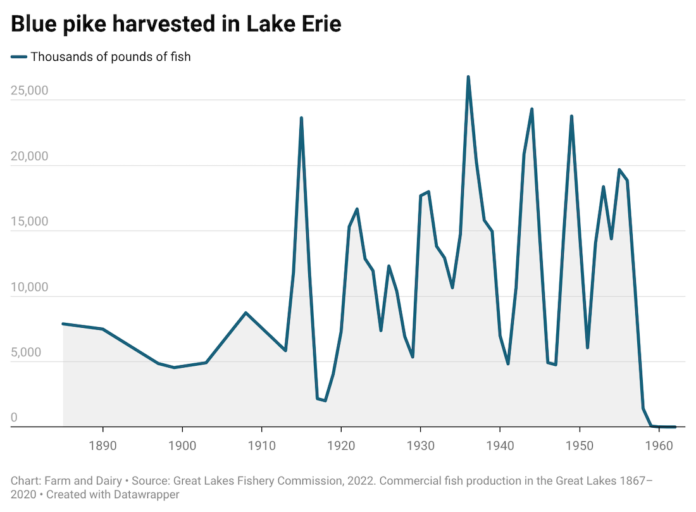

The Great Lakes Fishery Commission’s database lists the record harvest for blue pike as 26.8 million pounds in 1936. The harvests of the 1950s peaked at just under 20 million pounds in 1955 and remained above 10 million pounds through 1957.

Those numbers abruptly declined to 1.4 million pounds in 1958, and only 79,000 pounds in 1959.

“A few were caught through the 1970s,” Hartman said. “The last one was caught in 1983, and I’m not even sure where that was in Lake Erie.”

Walleye influence

From 1970 to 1972, it was illegal to harvest walleye in Lake Erie’s Western Basin because of their high mercury content, he said. Aside from the commercial fishing, pollution, frequent algal blooms, erosion and loss of wetlands and the introduction of invasive species may have all contributed to the blue pike’s sudden decline.

The blue pike was briefly considered an entirely separate species from the walleye, he said. But the science of genetics soon identified it as a subspecies of walleye. Still, the blue pike was identifiable to anglers and was targeted for both commercial and recreational fishing in Lake Erie, Hartman said.

There are black-and-white photos of fishing in the Sandusky Bay area that go back 100 years. In the 1850s, commercial fishermen primarily used seine nets cast from shore.

There was a huge change in the 1950s, and commercial fishing became more efficient. Now there was a wide variety of both wood- and steel-hulled boats, perhaps 30 or 40 feet from stem to stern. Gill nets were invented, with mesh openings of specific sizes that were “pretty much one hundred percent fatal” for any fish caught in them, Hartman said.

Aside from that, a lot of the romanticism about the blue pike probably comes from the history of recreational fishing, especially around Cleveland. Rowboats would go out from Cleveland Harbor at night, with lanterns hung over the side to attract emerald shiners. Pretty soon, “each boat would be surrounded by shiners and they’d catch boatloads of blue pike,” he said.

Both they and commercial fishermen could distinguish blue pike from walleye. The blue pike’s maximum size was 20 inches – it was usually under that – while walleye can grow to 32 inches. It was noted for its eyes, which were much bigger than a walleye’s. And its head was narrower, so there was a shorter distance between the eyes if you were looking at it from above.

Optical illusion

In “The Fishes of Ohio,” published in 1957, a book that is still used as a reference, author Milton B. Trautman said that color is an “unstable” way to identify walleye. Many fish, especially walleye, adapt to the amount of light and color in the water, Hartman said. He watched a walleye that was ghostly white when captured in murky water turn a very dark color when placed in a live well with clear water.

And therein may lie the reason for questions as to whether the blue pike is truly extinct. There is a pigment called sandercyanin that is bluish. It’s been identified in the mucus that covers the scales of some walleye. Anglers who call in reports of catching a blue pike have probably snagged a walleye with the bluish pigment, Hartman said.

But the name of the blue pike is doubly unstable; to quote Trautman, it was “a poor choice.” That’s because “all these fish are in the perch family, both walleye and blue pike,” Hartman said. So the blue pike was not a pike at all.

The blue pike also had a different lifestyle and eating habits than today’s walleye and seemed to prefer different parts of the lake.

Three lakes in one

Lake Erie is almost like three lakes in one, Hartman explained. “The Western Basin is mostly less than 35 feet deep. It’s so shallow that the wind and waves mix the water, so the temperature and water qualities are about the same from top to bottom.”

The Central Basin is deeper, with a spot that’s 80 feet deep north of Cleveland, near the Canadian border. But the Eastern Basin is really deep, with a place where the water is 210 feet.

In the Central Basin, when the surface water heats up in the summer, it creates a thermocline. The cold and warm water don’t mix, so “for a month or two, there’s low oxygen below the thermocline,” Hartman said.

In the Eastern Basin, both the upper and lower waters are well oxygenated, so fish can use the whole water column, he said. It’s warmer up high, colder below, but fish can choose where to go.

Today’s walleye migrate from the Western to the Central Basin, chasing their favorite prey, the rainbow smelt. However, the rainbow smelt didn’t show up in Lake Erie till the 1930s, so blue pike spent most of their time in the lake without smelt on the menu.

They probably went after those emerald shiners that the Cleveland anglers used for bait, Hartman said. And they probably spent most of their time in the deeper, clearer Central and Eastern basins.

Finally, while walleye can be found in all of the Great Lakes, the blue pike was only plentiful in Lake Erie, Hartman said.

“It’s a little less clear if they were also in Lake Ontario, or possibly the Niagara River,” he said. But none are there now, and no blue pike were ever kept in captivity for breeding purposes.

“The blue pike was unique to Lake Erie, and there’s no option for restoration,” Hartman said.

So, it will remain extinct, though not in the minds of some anglers.

“It’s definitely a legacy story,” he said. “It was an important fish for both sport fishing and the commercial industry. It was an important part of the Lake Erie fishing community.”

Great article, Barbara!

My dear old Dad used to regale us kids with stories of his own childhood in the 1930s getting all the blue pike they needed to feed his own large family fishing off Cleveland in Lake Erie. It was the Great Depression, and you needed all the quality protein you could get.

So very sad to see the blue pike gone.

Saw a half cooler full of blue pike on Kelleys Island in the mid to late 60’s