LANCASTER, Pa. — Trees in agriculture are often overlooked, according to Tracey Coulter, agroforestry coordinator at the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources.

“As my husband said, ‘Why am I planting trees? My pappy spent his lifetime pulling trees out of that field.’ But (when) you think about it, you look at a field and on a hot day, where are the cows standing?” she said.

“There have been studies that show that animals that have access to shade produce more milk, gain more weight. These are things that benefit the health (of livestock).”

Incorporating trees into agriculture is known as agroforestry, but it’s not a new practice; in fact, it’s an ancient one, dating back centuries. Agroforestry was the main point of conversation at the 2026 annual Pasa Sustainable Agriculture Conference held in Lancaster, Pennsylvania on Feb. 5-6.

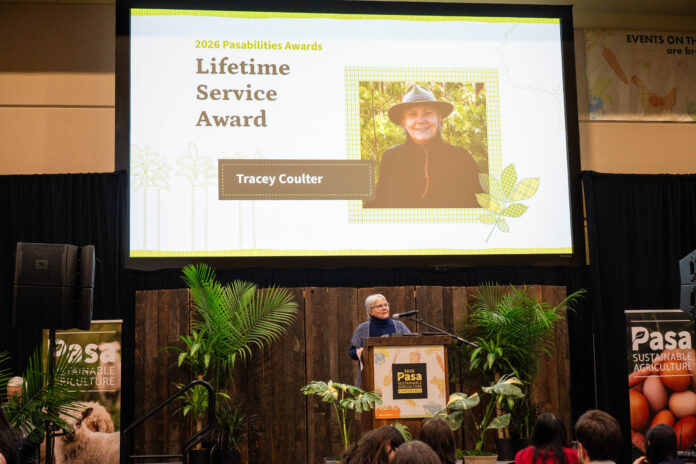

The event included an award ceremony where the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources’ first-ever agroforester, Tracey Coulter, received Pasa’s Lifetime Achievement award, as well as educational sessions discussing agriculture, including one about the old practice of tree hay.

Tree hay

Trees provide many benefits on the farm, including filtering out pollutants and providing shade for livestock — one of the many reasons why farmer Eli Mack has incorporated more trees in his 50-head beef cattle operation, Mack Farms, in Indiana County.

“It doesn’t have to just be open field or open pasture or a forest. It can be something that meets in the middle for the needs in the context of the farmer,” he said.

Mack recently embarked on another agroforestry journey: making fodder and tree hay.

According to Mack, up until the 1900s, tree hay was a common form of feed for livestock, a feed that predates the signing of the Declaration of Independence. But over time, this knowledge has been lost, which is why Mack gave a talk about his experience using fodder and tree hay on his 60-acre farm in Brush Valley, Pennsylvania, at the conference.

Mack first realized this connection between livestock and trees a few years ago when he witnessed his bull, Captain, bend a tree sapling down and eat the leaves.

“It was that moment that I was like, I know nothing,” Mack said about trees and livestock.

This experience jump-started Mack’s journey in using trees on his farm. In 2021, he started planting specific tree species on his farm for his cattle; last year, he planted 500 trees.

He also started using fodder and making tree hay — a good source of feed for cattle, sheep and goats.

Fodder is fresh branches and leaves used to feed livestock. One way this can be done is through creating fodder blocks: dense tree plantings that provide feed for livestock.

Tree hay, on the other hand, is similar to grass hay but instead is harvested, bundled, stored and dried branches of trees with the leaves on. It is best cut between June and mid-July when trees are at their most nutritious, Mack said.

Different trees can give different nutritional and environmental benefits: white mulberry is high in protein and comparable or superior to alfalfa as feed, while poplar trees are high in bio-mass and protein, great for droughts and are comparable nutritionally to timothy or fescue.

Other trees good for tree hay include oak, ash, honey locust, willow, black locust, elm, birch and more. Trees should be rotated for harvesting tree hay every year to let the tree growing back to full strength.

Mack notes, from personal experience, to be cautious about black cherry trees, as they can be poisonous to cattle if eaten when the leaves start to wilt. Wilted cherry leaves release cyanide.

To dry tree hay, the twigs should be bundled tightly and hung to dry in a barn or on racks.

According to Mack, tree hay is especially beneficial in the cold winter months.

“In the wintertime, we’re out on pasture, there’s nothing green, (the cattle) ate all the grass and we’re feeding stored hay. It’s okay, it’s going to get them through, but it’s not what they truly need,” he said.

“We can pull stored tree hay out of the barn and get some of those nutrients and minerals back in the animals at a time of year when they’re not accustomed to having that.”

Mack adds that if a farmer’s grass hay harvest is lacking (like from drought), tree hay is an alternative, nutritious feed source.

Although it may be intimidating to start something new, he suggests taking it one step at a time.

“You don’t have to run out here and do a big project planting trees. Start with the trees you have. Some farmers have marginal land that’s growing, or maybe they have a stand of wood somewhere that could be managed or harvested in some capacity to start them down this road” he said.

Agroforestry

There are multiple ways a farmer can practice agroforestry other than tree hay. For decades, this was Tracey Coulter’s job: spreading the word about different agroforestry practices.

But, unlike most people, Coulter didn’t take the traditional route to becoming an agroforester. She was 46 years old when she first started attending forestry school at Penn State University.

In 2001, she graduated with an associate’s degree in forest technology from Penn State and went on to earn a bachelor’s degree in forest science and a master’s degree in forest resources from the university.

“Tracey’s gift, perhaps learned in this non-traditional path, was to get other people as excited as she was about the ancient but re-emerging practices of agroforestry,” said Sara Nicholas, policy specialist at Pasa Sustainable Agriculture, who honored Coulter at an award ceremony on Feb. 5.

Coulter, along with Penn State Educator Steve Bogash, received the Pasa’s Lifetime Service Award.

While pursuing these degrees, Coulter was hired as the state DCNR’s first agroforester in 2004 where she focused on the practice of riparian buffers — strips of trees, shrubs or grass planted along streams and other bodies of water to protect against and filter out agricultural pollution.

Over the years, Coulter has traveled across the region to assist farmers with agroforestry projects, attend conferences and give presentations, Nicholas said. Her extensive work in this field has protected water sources, built up soil and supported biodiversity.

Since she was hired as an agroforster over two decades ago, the practice has since expanded to silvopastures, alley cropping, forest farming and more.

Coulter recently retired, but is excited for the future generation of agroforesters that is more plentiful than ever before.

“What’s changed (about agorforestry) is that it’s more acceptable. We have more people out there doing the work and helping to educate people working with farmers,” she said.

Next generation

Austin Unruh, of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, is one of these next-generation individuals working to spread the practice of agroforestry. Unruh opened up his business, Trees for Graziers, in 2017, where he works with farmers to integrate agroforestry practices on their farms.

Initially, he wanted to work as an agroforester, but at the time, no one was hiring. That was when he reached out to Coulter, who connected him with other agroforesters in the state.

“I learned that there was a need for people to work in maintaining buffers after they were planted along the streams. And that’s how I got started,” Unruh said.

Over the years, his business grew to working with farmers with grass-fed dairy and beef cattle to plant trees in their pastures. These trees often include fast-growing shade trees like hybrid poplars, willows and black locusts, and long-term trees, such as honey locust, persimmon and mulberry.

These long-term trees will drop fruit and act as an additional source of feed for livestock. Today, helping farmers plant trees is his main focus of the business; since opening, he has helped over 50 farmers plant trees and has consulted with dozens more.

“It turns out that if you can make this easily accessible to farmers, there’s a lot of people who want to do this,” Unruh said. “Our goal has been to make this as easy as possible.”

(Liz Partsch can be reached at epartsch@farmanddairy.com or 330-337-3419.)