SALEM, Ohio — As the spread of highly pathogenic avian influenza enters its fourth year, experts who track the disease are continuing to express concern over the virus’s capacity to jump to animals that aren’t birds.

“The one thing that has been different is the potential to see it more in other animal species, especially in dairy herds,” said Joe Moritz, a professor of dairy science at West Virginia University.

The disease impacts poultry, such as chickens or turkeys, but has been detected in pigs, cattle and even humans, raising alarms among farmers, researchers and government officials.

“For West Virginia, this fall migration has had more wild bird detections than previous migrations,” added Erika Alt, West Virginia’s assistant state veterinarian.

To be clear, the avian infectious disease can be devastating to poultry farmers. Entire flocks have been euthanized to keep the highly contagious sickness from spreading, and every case of bird flu detected in chickens and turkeys destined for kitchen tables threatens to send food prices a little higher.

But the possibility of cross-species contamination creates an element of unpredictability to an infection already denting farmers’ bottom lines, according to experts

Unexplained spread

Bird flu has been detected in cattle in California, Texas and Wisconsin in the past few months, Alt said, although none in the past 30 days. The first case of bird flu in a dairy herd was detected in March 2024 and sent shockwaves through the agricultural community. It was initially unknown how the virus was being spread in cattle or what it meant for consumers. In total, 1,084 cases were detected in dairy cattle in 19 states, including one case in Ohio early on.

Pasteurization kills the virus, stressed Brian Baldridge, director of the Ohio Department of Agriculture, which means there is virtually no possibility of catching the bird flu from drinking milk. But infections in animals are still disruptive.

“Agriculture is a critical part of our economy,” he said.

Pigs can also be infected by the disease because they have a respiratory tract similar to that of birds, said Moritz, although bovine infections have been limited.

“So far so good,” he said.

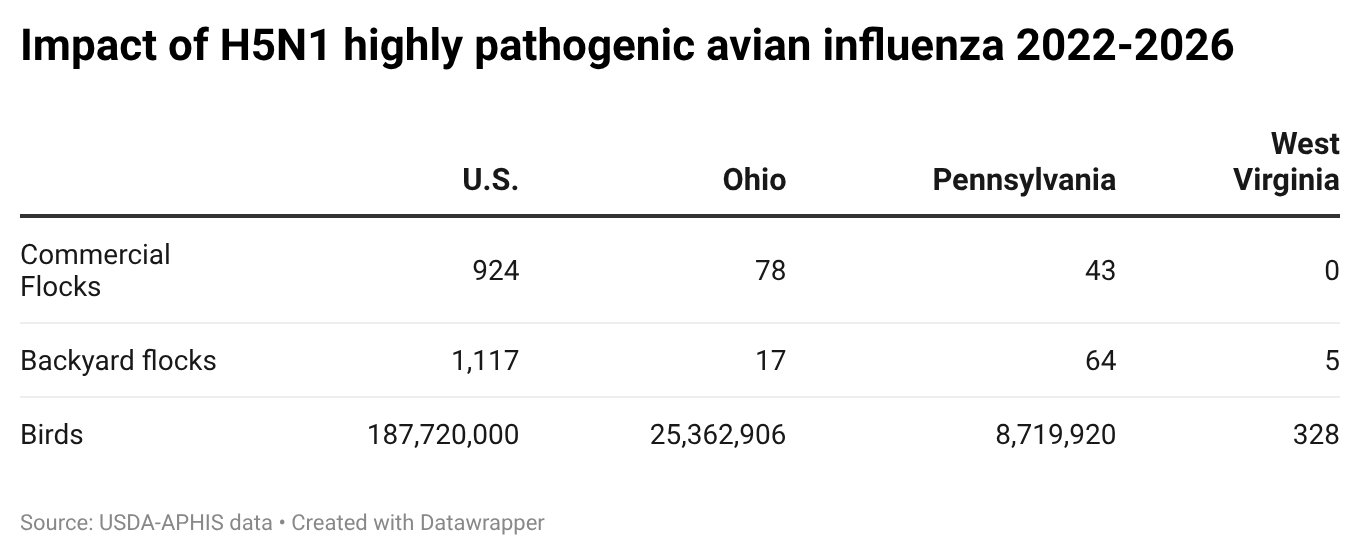

Since the bird flu outbreak began in the United States in February 2022, the virus has killed 187.72 million birds in all 50 states and Puerto Rico, according to USDA data.

The disease has been detected in Pennsylvania, Ohio and West Virginia in wild and domestic birds over the past several months, mostly in backyard flocks, although a case was reported Jan. 28 in a flock of 1.5 million egg-laying hens in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. Bird flu was also the suspected cause of 70 black vulture deaths in Clermont County, Ohio, and 400 snow geese deaths in Erie County, Pennsylvania, in December.

Can it infect humans?

Bird flu has been detected in a small number of people, mostly those working closely with infected livestock, but experts say that widespread human infection isn’t a concern yet.

The virus affects the respiratory tract, and “humans don’t have the same receptors as birds,” Moritz said. “But there have been mutations.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has counted 71 cases in humans and two deaths since 2024.

What will this year look like? The severity of this year’s bird flu season is a matter of debate. Everyone interviewed for this article agrees that we will see it spread this year, but how bad it will be remains to be seen. The disease spreads from wild birds to poultry and broiler chickens during migration seasons in the spring and the fall.

“That’s when we see the uptick,” Alt said.

What about the vaccine?

As of now, poultry can’t be immunized from the virus, and some of the vaccines in development are impractical, Moritz said. One such vaccine would be administered through the nose, he said.

“An average [poultry] farm can have thousands of birds,” and giving each of them a nasal vaccine would be a struggle, Moritz said.

But researchers are working on alternatives. West Virginia University was recently awarded a $2 million grant to develop an edible vaccine, Moritz said.

There’s another issue with vaccinating poultry — trade implications. There is a concern that vaccinated birds could be infected with the bird flu but not show clinical signs. As a result, many countries, including major importers of U.S. poultry, do not recognize birds as being free of the flu.

What can you do about it?

The strategies to prevent avian flu infections haven’t changed, officials stress.

“Wash everything, then disinfect,” said Gregory Martin, a Penn State Extension poultry educator.

Minimizing contact with wild birds and keeping foreign objects out of chicken coops and poultry barns remains the order of the day, Baldridge said. That means, among other things, going into those spaces with clean clothes and making sure delivery trucks and other vehicles are thoroughly washed.

“The number one defense is biosecurity,” he said.

Farmers should also keep visitors to a minimum, Martin said.

“You don’t know where the UPS man has been,” he said. “Always try to keep them relegated to some place other than where the birds are.

• • •

The U.S. Department of Agriculture is offering a series of free webinars focused on biosecurity best practices to help prevent the introduction and spread of highly pathogenic avian influenza on farms.

The next, “Double Down on Biosecurity: Preventing Bird Flu in Poultry,” will be held at 2 p.m. on Jan. 30. For more information and to register online, visit tinyurl.com/3ep3dwzx.

Strong biosecurity makes for the best defense against the highly pathogenic avian influenza. Join experts at the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service to learn about the latest in biosecurity best practices, complete with resources for poultry farms of all sizes, such as biosecurity assessments for farms with 500+ birds. Speakers include Poultry Staff Veterinary Medical Officer Nancy Hannaway of APHIS Veterinary Services, Management and Program Analyst Jacob Smithson, also of APHIS Veterinary Services, and David Marks, Assistant State Director of APHIS Wildlife Services.