MILLVALE, Pa. — Each wall in St. Nicholas Croatian Catholic Church in Millvale, Pennsylvania, tells a story: a miner dead from an accident, beggars asking for food, mothers weeping next to tombstones, Jesus stabbed by soldiers.

Although cruel on the surface, each one represents a larger picture, extending beyond the church walls, to detail the immigrant experience in America, the sacrifices of war and the cost of both.

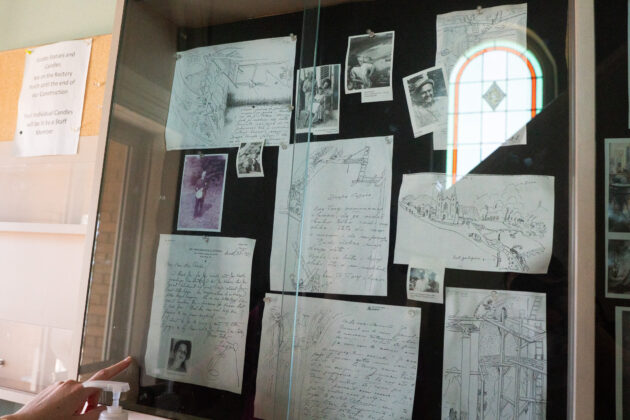

The church, located on the outskirts of downtown Pittsburgh, is unlike many others in the region; it was the first Croatian Roman Catholic church in the country and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. It is most famous for its murals painted by Maxo Vanka, a Croatian immigrant, in the 1930s, which intertwine traditional religious depictions with the American immigrant experience and war.

The murals have been deteriorating rapidly over the years, but since 2008, the Society to Preserve the Millvale Murals of Maxo Vanka has been restoring them through state and federal grants. The organization is currently looking for donations to fund the last leg of work needed to complete the mural restorations, because, to them, there is no greater piece of art than art that is timeless.

“They are unique because they were painted back in ‘37 and ‘41 but they still feel contemporary. They still reflect what’s happening in our world today,” said Anna Doering, executive director of The Society to Preserve the Millvale Murals of Maxo Vanka. “They’re important because they tell the story of the time they were painted in. They represent the Croatian heritage and the immigrant contributions to America back in the day.”

History

St. Nicholas Croatian Catholic Church was established in 1900 to meet the demands of a growing Croatian population in Pittsburgh. At the time, it is estimated that the Croatian population in Pittsburgh ranged from roughly 40,000 to 200,000.

Soon after it was built, however, disaster struck: a fire burned down most of the original church. A smaller church was rebuilt a year later, but when Father Albert Zagar became priest in 1931, he saw the blank, plaster walls as a problem.

After seeing some of his work, Zagar asked Vanka to paint murals in the church; he wanted to add more life to the church while representing the local community. Maximilian Vanka spent the first eight years of his life working as part of a peasant family before his biological grandfather lifted him out of poverty and took him under his wing.

He immigrated to the United States in 1934 at the age of 45 when his American wife, Margaret Stetten, convinced him to move to New York and escape the growing threat of fascism in Croatia, then part of Yugoslavia. His experience growing up in poverty and being an immigrant would shape his work throughout his life.

He started the first set of murals in 1937, which included one of his most famous pieces, “Immigrant Mothers Raise Their Sons for American Industry.” The second set of murals was painted in 1941, including “The Croatian Mother Raises Her Son For War.”

In total, Vanka painted 25 murals in the church that blend traditional depictions of the crucifixion and pieta with the immigrant experience in America during the industrial revolution and war. Some of the murals are based on real-life incidents. Vanka painted “Immigrant Mothers Raise Their Sons for American Industry” after a coal mining accident in Johnstown, Pennsylvania.

Other paintings speak to the harm caused by World War II and Vanka’s anti-war perspective, including “The Croatian Mother Raises Her Son For War,” where mothers wear Croatian mourning dresses and weep over an open casket surrounded by a field of unmarked gravestones, and “Christ on the Battlefield,” where soldiers stab a crucified Jesus. In another painting, “Mary on the Battlefield,” Mary is seen bending the bayonets of attacking soldiers.

The murals speak to the casualties of war and the cost immigrants pay, whether they leave or stay. For Jessica Keistars, one of the art conservators at the church, the murals showcase a universal immigrant experience that many people can connect to.

“I had a great grandpa who worked in mines and got really, really hurt and then died a couple years after (due to) his injuries. One of the other women on the team (of conservators) her grandfather worked in the steel mills,” Keisters said. “I think we’re all connected to it, that even if you are not Croatian American, you can see the story of the journey from one place to America, and how there’s hardships on both ends.”

Reconstruction

Over time, the murals started to incur water stains, soot build-up and damage from weather-related events like Hurricane Ivan, which caused extensive flooding and damage in Millvale. Vanka also used commercial-grade paint on the plaster walls; the combination has led to “efflorescence,” in the murals — a build-up of salts the plaster excretes in the presence of moisture.

The Society to Preserve the Millvale Murals of Maxo Vanka was established in 1991 by church members as a way to invite foundations and other organizations to get involved in restoring the deteriorating murals. The work to restore the murals began in 2008, a meticulous, multi-step process conducted by 14 art conservators and conservator technicians.

First, an art photographer will take a photo of the mural before the conservators put up a scaffold, said Keisters. The murals are then cleaned by brushing off dirt and applying a water-based solution. Afterwards, conservators will fix gaps from cracked plaster with fill material and retouch damaged areas with watercolor or pastel paint — this paint can be reversed or retouched later if needed.

According to Doering, the work to restore the murals has been conducted as funding has become available. The church has received funding from the Samuel H. Kress Foundation, individual donations and through state grants like a Pennsylvania Department of Community and Economic Development grant.

In 2022, the Society to Preserve the Millvale Murals of Maxo Vanka applied for a Save America’s Treasures grant, administered by the National Park Service, and was awarded roughly $470,000 by the Institute of Museum and Library Services.

“The damage to the murals was continuing, so we wanted to address it as fast as possible,” Doering said, about applying for the grant. In the past three years, the funding has allowed the organization to complete some of its most tricky murals, including “Transcendent Vision,” on the ceiling of the church and sections on the high walls.

The society had $140,000 left of the grant to be reimbursed, but it was canceled by the Institute of Museum and Library Services in early April. The federal agency said it terminated the grant to realign with President Donald Trump’s executive order “Continuing the Reduction of the Federal Bureaucracy.”

On April 30, however, the grant was reinstated by the Institute of Museum and Library Services and the Society to Preserve the Millvale Murals of Maxo Vanka submitted for its final reimbursement.

But, Doering is unsure how quickly it will get approved. Reimbursements are typically granted within 3-5 business days, but she is concerned it will take longer with the reduced staff at the federal agency. The Institute of Museum and Library Services, initially made up of 75 employees, is expected to reduce its staff by 80%. The agency laid off its employees to comply with Trump’s executive order to reduce the size of seven federal agencies.

Fortunately, the church has already raised enough money to match the remaining funding. However, Doering said the society is “planning for the worst scenario” and is accepting more donations as work continues on the final phase of murals.

After conservators finish the mural they are working on now, the last mural will be the center mural by the altar. Doering estimates work will begin on that, most likely near the end of 2025. Doering adds that the biggest impact of initially losing the federal funding has been redirecting their efforts elsewhere before completing the murals.

For instance, the society will be installing climate control technology, with the goal of preserving the murals for the long term, in June instead of starting on the final mural in summer. To spread the word, the Society to Preserve the Millvale Murals of Maxo Vanka hosts tours for the public and educational programs for middle school and high school students.

“We consider this a test. It’s really a chance to talk about justice and injustice and the impact of war. What do you see in these murals, and how does that make a connection to what’s going on your own life today?” said Doering. “Everyone can walk in and find their story in the mural.”

The society recently held a “Community Day” on April 27 where visitors could view the murals, participate in raffles and eat food. Barbara White, a resident of Pittsburgh, was there on community day with her friend from Columbus, Ohio.

This wasn’t her first time visiting, though. White has been coming to St. Nicholas Croatian Catholic Church for roughly 30 years now. She has seen the improvement in Maxo Vanka’s murals, which she said were in “much worse condition,” and is stunned by the progress conservators have made.

But why does she keep coming back all these years later? To remind herself that sometimes history isn’t always history.

“These murals really speak to what is going on today. We’re involved in several wars, if not genocide, and people need to understand that this is not something new. And so many of the people pictured in these were immigrants. Immigrants are important, they built this country. I think it’s important as well to support immigrants today,” White said. “It really (shows) the more things change, the more they stay the same.”

To donate, visit https://themaxovankamurals.ddock.gives/?showBg=. For more information, visit https://vankamurals.org/.

(Liz Partsch can be reached at epartsch@farmanddairy.com or 330-337-3419.)