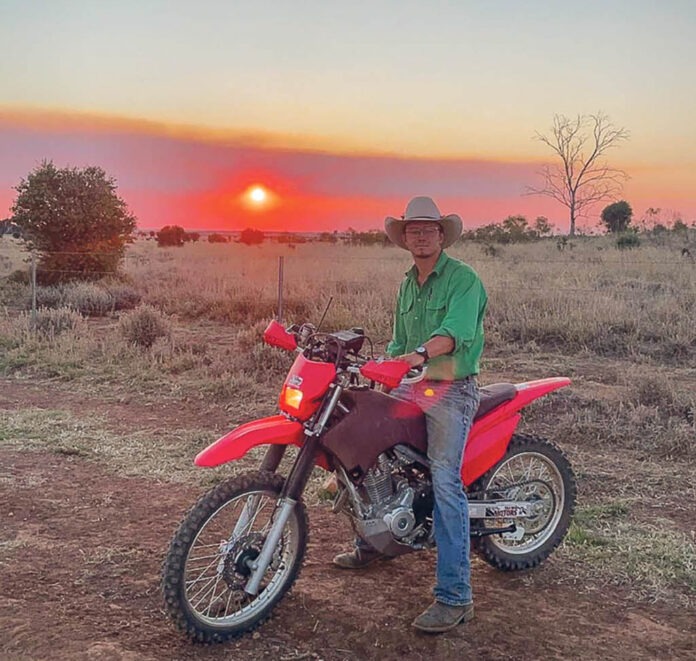

The term cowboy is often reserved for cattle ranchers with deep roots in the American West, where livestock graze across hundreds of acres. In Ohio, where cropland far outweighs grazing land, the title isn’t inherent. Except, perhaps, for Hayden Johnson.

The sheep showman and recent animal science graduate from Richmond, Ohio, left the States in June to work on a family ranch running thousands of Brangus cattle in Queensland, Australia.

Rolling down red-dirt roads on motorbikes and ATVs, his days involve traversing hectares of land to check cattle, inspect water points and assist with the artificial insemination of heifers.

Finding his way to the other side of the world wasn’t a distant dream. He grew up hearing stories about his father working on Australian farms after college.

“As graduation got closer, I knew I wanted to do something in agriculture, specifically livestock, but I didn’t know the exact path,” Johnson said. He ended up following his father’s footsteps, an adventure of a lifetime repeated one generation later.

Finding his way

With help from Ohio State University’s Delta Theta Sigma alumni, Johnson connected with Gidyea Brangus Farm and the Forrest family, who now host him.

“I’ve had a lot of opportunities to do everything they’re doing,” he said.

From June through the coming spring, his environment looks far different from America’s ranching front. The 3,000-head commercial herd focuses on building seedstock for feedlotters and processors. Doing that in Queensland means facing extreme summer temperatures, often 105°F.

His companions in the outback include kangaroos, emus and other wildlife that roam the same land as the livestock — many of them able to match a person’s speed or height.

“There are plenty of snakes, too,” he said.

The region resembles the rangelands of the Rocky Mountains, with 65% of its land used for cattle. But unlike the Rockies, Queensland sits on Australia’s east coast. Split into paddocks and pasture by long stretches of dingo fence, the area’s immense land base makes cattle production possible at a scale the U.S. population density can’t match.

“We’re a lot more population-dense in the U.S., so we don’t have as many options,” he said.

In the outback, Johnson works with the Forrest Family and their three sons when they’re home from boarding school in the closest city. Like many ranching operations, the ranch is family-run, but Australia’s nearly 10 million-head cattle inventory is often leaving the country, heavily supplying the grass-fed export market.

“In the U.S., we’re in the high 90% range for grain-finished beef. Over here (Australia), it’s significantly less — around 40% of steers end up grain-finished. It’s all about consumer preference,” Johnson explained.

Before processing, he said, cattle are moved to special paddocks of legume-grass forages like Leucaena. Known for being drought tolerant, highly productive and the nutritional equivalent of clover, it helps produce fatter cattle with shinier coats. The country is also known for its massive sheep population, roughly 60 million more than the U.S.

But the energy of the livestock marketplace is visible everywhere, he noticed.

“You can be watching the nightly news and there’ll be bull sale commercials scrolling across the TV,” he said— something he rarely sees at home.

Dominant breed

As a certified Brangus operation, the ranch’s genetics hold high value. While most of the herd is Brangus, “ultra blacks” also make up the herd, seedstock with a higher percentage of Angus.

College training at Ohio State helped Johnson contribute to the operation’s breeding program, which included 120 Brangus stud females. In Australia, he explained, producers are allowed a wider range of reproductive techniques.

“One thing that really surprised me — something I didn’t even think would be different — was their regulations on synchronisation drugs and hormones,” he said, which are less restrictive to account for the Brahman breed’s longer postpartum recovery.

In August, Johnson participated in the artificial insemination of 500 heifers, in addition to the ranch’s annual bull sale. While this wasn’t his first international experience — he previously visited the livestock industry in Scotland — each trip, he said, helps him think about “what we can do differently at home.”

It’s a perspective that he said communities in all rural areas need.

“What I’ve found between here and home is that no matter what someone in agriculture is doing, they’ll always talk about it, show you how they’re different, and want to figure out how they can change.”

Outside of work, Johnson has explored the Great Barrier Reef, national parks and many of the same adventures his father once experienced. He’ll return home to Ohio this spring with new AI skills, grass-fed beef experience and a little red dirt in his boots.

Seeing agriculture from a new angle, “it kind of opened my eyes to my true love for the livestock industry,” he said.