Halloween, that spooky holiday that festers with images of arched-back black cats, spiders dangling from webs and bats looking to land in big hair. While those felines are imagined to bring bad luck or riding shotgun on a witch’s broom, and some cringe at the thought of creeping arachnids and swooping winged mammals, these fears are far out of proportion to the threat.

Then again, most of us have heard the horror stories of abandoned pets starving or being injured, but what if those pets went rogue and Cujo crazy and are stalking the backlands just waiting for the perfect opportunity to strike?

It all started like a horror movie. A seemingly docile creature that the owner can no longer care for is intentionally abandoned in a remote area, a situation that should anger most of us. Likely both confused and frightened, it’s suddenly forced to fend for itself and begins its search for food. Following a nightmarish script that could have been inked by Stephen King or Dean Koontz, it begins to grow. Its appetite blossoms and expands as it begins to dominate its surroundings.

As luck would have it, it finds a similarly discarded creature of its own kind and offspring result. Their young, never having been held by a human, are born to hunt and kill. Reaching nearly 200 pounds, they need to feed. They move silently through the countryside in search of their next hapless victim.

Their attack is a sudden ambush, as they use their great strength to choke the life from their prey, and with a grotesque gift from Mother Nature, their jaw unhinges to allow them to swallow their victim whole. In my mother’s words, “this gives me the heebie-jeebies” — but this isn’t a King or Koontz novel, this story is real.

Exotic to wild

Burmese pythons that were sold as exotic pets have found their way into the wilds of South Florida. Once calling a glass terrarium home, these snakes either escaped, grew until they were too much to care for or the owner developed a reptilian set of morals and just kicked them out to live off the land — a land they found most welcoming and a climate befitting their tropical heritage.

The Burmese python is now found across more than a thousand square miles of southern Florida, including Everglades National Park, Big Cypress National Preserve and Collier-Seminole State Forest. This isn’t just a couple of snakes; estimates indicate they number into the tens of thousands — and they’re breeding more wild offspring each year.

Native decline

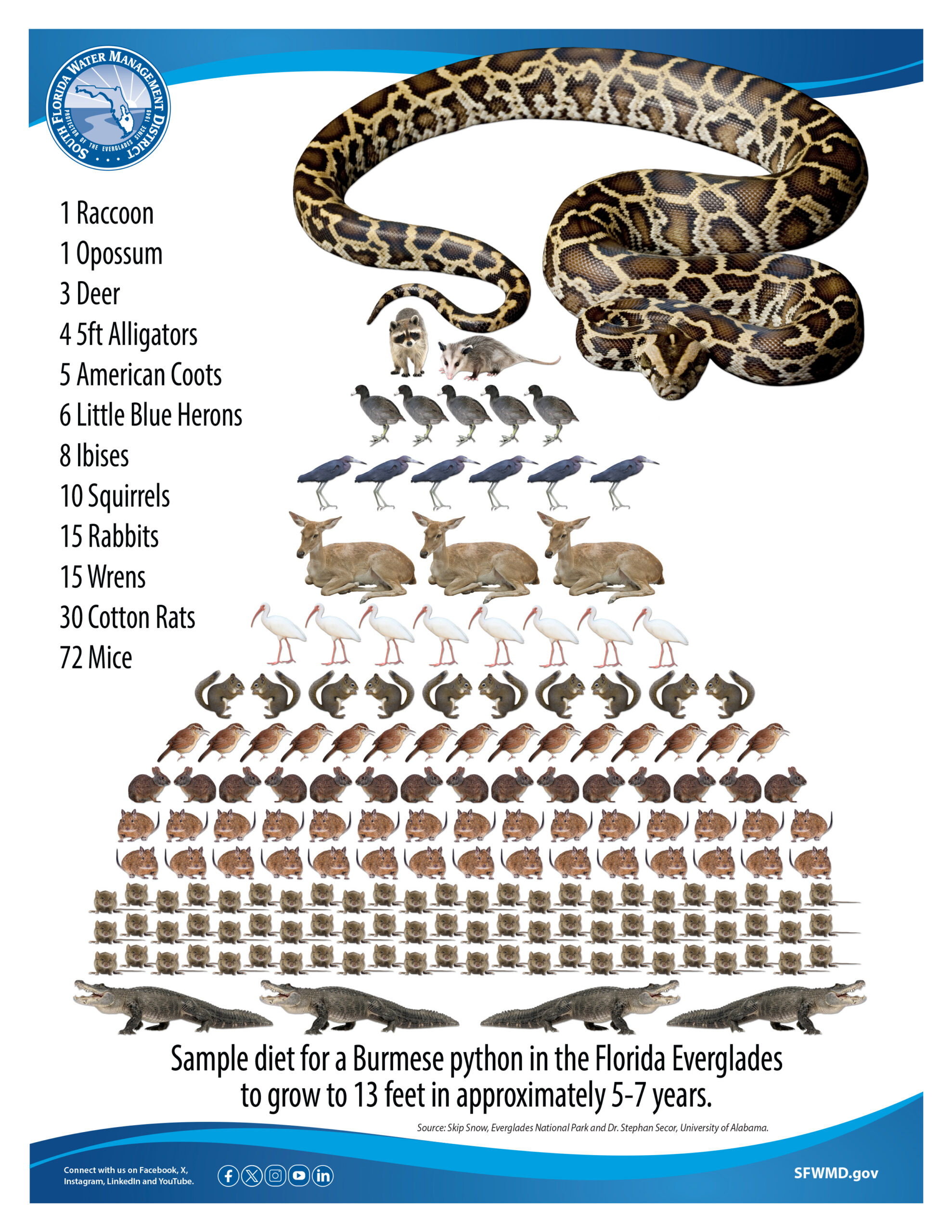

While they do compete with native wildlife for food, their primary food is that wildlife. According to the U.S. Geological Survey, severe declines in native species have occurred in the remote southernmost regions of the Everglades. Large constrictor snakes haven’t existed in North America for millions of years and their impact on native species is staggering. According to the National Wildlife Federation, “These non-native invaders put over 40% of threatened or endangered species at risk.”

An eerie and unnatural silence now envelopes portions of the Everglades where the busy raucousness of wildlife’s daily life was once the norm. To an observer of nature, the quiet is deafening.

A study conducted in 2012 indicates that since 1997, raccoon populations dropped 99.3%, opossums 98.9%, and bobcats 87.5%. Marsh rabbits, cottontail rabbits and foxes effectively disappeared. Larger Burmese pythons have been found with entire deer inside their bodies.

How big can a Florida Burmese get? Two feet long upon hatching, they grow quickly to 10 feet, and then their growth slows considerably — slows, but doesn’t ever really stop. Snakes over 20 feet and weights of 200 pounds have been found, with the largest tipping the scale at 215 pounds.

As a constrictor, the Burmese uses its strength to wrap and squeeze the life out of its prey and then swallows the animal. Human fatalities from non-venomous snakes are very rare, likely averaging one or two per year worldwide. Constrictor-snake fatalities in the United States have been from captive snakes and due to careless handling or confinement.

I doubt those statistics take into account those that die of exhaustion while sprinting away from such a sizeable slithering serpent sliding silently their way. While there has never been a human death in Florida attributed to a Burmese, the risk can’t be ruled out.

The situation is similar to that experienced with alligators; attacks are improbable but possible anywhere that the animals are active. The snakes are most likely found near water, including canals, ponds and lakes — especially in remote areas and those with heavy vegetation surrounding the edges. A bigger worry is that Burmese pythons have become the most destructive and harmful species in America’s Everglades.

As if those novelists might be considering a sequel, the discovery of several African rock pythons has added to scientists’ worries. You see, Burmese pythons are a relatively gentle sort — for being an overzealous hugger — that at least doesn’t show much aggression toward people.

On the other hand, rock pythons aren’t so warmhearted toward upright primates. They’ve also been known to interbreed with the Burmese and the phenomenon “hybrid vigor” becomes a concern — a condition which may possibly unleash volatile recessive genes of aggression. I’m not feeling too good about this…

Experts say, “… that the simplest and most sure-fire way to reduce the risk of human fatalities is to avoid interacting with a large constrictor.” Thank you, Captain Obvious … but with that said, Florida is always looking for folks that are willing to do a little close-up snake interaction — as in “go catch some very large constrictor type snakes.” Does that seem contradictory to you?

Management

Over the past few years, the South Florida Water Management District has been taking aggressive action to protect the Everglades and removing invasive pythons from its public lands. While eliminating the animal is unlikely, number control is the hopeful outcome.

One of the programs that they’ve been using is the Florida Python Challenge; this year, it ran from July 11 to July 20. The annual 10-day competition is hosted by the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission and the South Florida Water Management District.

According to their posting, “An exciting addition to this year’s event is the inclusion of Everglades National Park as one of eight official Florida Python Challenge competition locations” — like playing with a 200-pound snake isn’t exciting enough and you might need something more to get you pumped up for action.

But this removal program and others conducted by these agencies are incredibly important to our nation’s natural resources. The python threat to the Everglades ecosystem is more than just the presence of the snakes. It’s the artificial introduction of an invasive apex predator which preys upon the wildlife that lives there, including wading birds, mammals of all types and sizes and other reptiles. Their aggressive predation robs Florida panthers, raptors, bobcats and other native predators of their primary food sources and threatens to tip that predator-prey balance.

During one study, researchers released 95 adult marsh rabbits in areas of the Everglades known to harbor pythons. Within 11 months of the release, the study showed that pythons accounted for 77% of rabbit deaths.

During last year’s Florida Python Challenge, more than 850 participants removed nearly 200 destructive pythons from public lands.

Burmese pythons were first sighted in the Florida Everglades in the 1970s; their introduction a result of the pet trade. Once confined to Everglades National Park and Miami-Dade County, pythons are now found in much of South Florida. Pythons exist from Monroe to Palm Beach counties, and from western Broward County to Collier County.

If you happen to winter in the Sunshine State or if you have friends that you’re not particularly fond of, the South Florida Water Management always seems to be taking applications for snake hunters. The Python Elimination Program accepts applications for new python removal agents who work on designated lands across South Florida, including Monroe, Miami-Dade, Broward, Collier, Hendry, Lee and Palm Beach counties. Interestingly, due to the high volume of applications they receive, they’re unable to respond to every applicant but will notify folks if selected. Who knew there would be a line at that door?

For those of you already packing, apply at www.sfwmd.gov/our-work/python-program. If you aren’t one of the lucky ones to be chosen, the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission might give you the green light to hunt them on 22 wildlife management areas; no permit required. Visit the Commission at myfwc.com/wildlifehabitats/nonnatives/python/ for current laws before heading out.

While you’re down there, you may want to swing by the pizza parlors in Naples. They’re offering “Everglades Pizza,” which features bites of Burmese, a little alligator and boned frog legs.

If you prefer to be your own chef and python nuggets, sauteed Burmese or poached python curry sounds yummy, visit allenrsmith.com/2021/08/04/burmese-python-its-whats-for-dinner.

Would these match best with a white or a red?

“Every great story seems to begin with a snake.”

— Nicolas Cage