Over the last two decades, an energy company founded in 2001 has become the largest natural gas well owner in the U.S. — without drilling wells.

Diversified Energy has bought about 70,000 mostly conventional oil and gas wells across the U.S., largely in the Appalachian Basin. The company now owns more than 7,000 in Ohio, 22,000 in Pennsylvania and 23,000 in West Virginia, making it a big player in the region’s oil and gas industry.

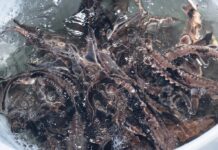

Many of these wells are already decades old, long past their early days of high production levels. Some have fallen into disrepair over the years. Some don’t look like much.

“When I bought my first … my wife couldn’t believe I was taking out home equity to buy a pipe in the ground,” said Rusty Hutson, founder and chief executive officer for Diversified Energy.

The company focuses on keeping these older wells up and running as long as possible by repairing and maintaining them. Diversified estimates on average, the wells it owns can keep producing for another 40 or 50 years.

“We don’t need as many new wells if we’re keeping the wells in this country that have capable reserves producing,” Hutson said.

Older wells

Diversified’s model is atypical, but it’s not uncommon for wells to change hands several times over their life spans, said Tom Murphy, of Pennsylvania State University’s Marcellus Center for Outreach and Research.

Wells usually produce a lot up front, when they are first drilled, then decline dramatically, but continue to produce at a lower rate for decades. There are conventional wells that have been producing for upwards of 100 years, so many wells, depending on when they were drilled, can be expected to produce for decades, he added.

“So, the companies that do the work in the beginning and make a profit on that start selling some of those wells to others that have different business models … but still produce those wells in a profitable way,” Murphy said. “It’s just a different model.”

Diversified is based in Alabama, but Hutson is from West Virginia and bought his first well there. The conventional wells that make up most of Diversified’s purchases may be as old as 30 or 40 years. Most were drilled in the 1970s or ’80s.

For a company with a business model focused on drilling new wells, or a smaller company without as much capital to spend on maintaining and upgrading wells, it might not make sense to hold onto them. But for a company with resources available to fix up and maintain the wells, they can continue to produce at lower rates for a long time. And because Diversified owns so many of them, the lower rates add up.

Work

What, exactly, Diversified does with a well once it buys it varies. If a well is in fairly good condition, it might just keep going along the way it has been. Wells that need repairs or upgrades go on a list. They might end up near the top of the list if they have potential to be very productive after they get some attention.

The company can determine that partly by looking at the well’s history on state websites. Depending on how close to the top of the list a well is, it could get fixed up very quickly, or it could take a while for Diversified to get to it.

“So we can see, well, this well averaged, when it was newer, 300 barrels a year, or whatever it is, and then now we see five years of zeroes. So then, this becomes a good candidate,” explained Tom Vosick, vice president of operations in Ohio for Diversified. “That’s how we base our decision on which well we want to go to first, and we just keep working down.”

Location also plays a part. It doesn’t make sense to move equipment all over the state and back again, so workers will work on several wells in one area before moving onto another area.

One conventional well, near Caldwell, Ohio, was still producing when Diversified bought it in 2018. But the pump in the well had been down for about five years, so it was declining and not working efficiently.

After Diversified bought it, they pulled that pump out and put a new one in. The well went from producing 1,000 cubic feet of natural gas per day, to 3-5,000 cubic feet per day. The well site is also producing about three or four barrels of oil each week.

“So, basically, what we spent, probably $6,000 — we’re going to recoup probably $20,000 off of just this well this year,” Vosick said.

Sustainability

Often, once those improvements or fixes are done, it doesn’t take a lot of maintenance to keep a well going. A newer, larger well site, like a well Diversified bought from EdgeMarc Energy near Woodsfield, Ohio, might have someone on-site every day, keeping an eye on it and making sure things are running smoothly.

For older, smaller sites, a well tender has a list of about 100 wells to take care of, with an average of about 20 well visits every day.

Conversations about the oil and gas industry often lead to concerns about environmental stewardship and sustainability. Older wells, in particular, sometimes have issues with methane leaks. Hutson views fixing them as one important part of that — the company bought detectors in late 2021 for well tenders to check for methane leaks at their well sites — as well as following state and federal regulations and preventing and cleaning up spills.

He also said financial sustainability allows Diversified to take care of wells so they can keep producing and provide royalties for landowners.

Plugging

Sometimes, wells really are at the end of their lives. States have regulations that require companies to plug wells that are no longer producing at commercial levels. That takes time, and money — Murphy said plugging a well in Pennsylvania can cost anywhere from $10,000 to $100,000.

Keeping much of its well plugging in-house, instead of hiring third party companies to handle it, in addition to having wells spaced out over a schedule to be plugged, also helps Diversified keep its costs down when it comes to retiring wells.

Diversified puts wells that need to be plugged on an asset retirement list and are scheduled to be plugged — the company has deals with individual states to do a certain number each year. If there’s a safety or environmental issue, the well goes to the top of the list.

Diversified currently plugs about 20 wells in Ohio each year, and plugged a total of about 115 in 2021. The company has committed to retiring at least 200 wells per year across the Appalachian Basin by 2023.