SALEM, Ohio — More than 15,000 U.S. Department of Agriculture employees have left their jobs since March, part of a sweeping reorganization plan that remains stalled by a court challenge.

The reduction in force comes amid nearly $7 billion in proposed budget reductions for the department unveiled by President Donald Trump’s administration on May 30.

Framed in the budget summary as a push to “safeguard our country from fiscal ruin,” the budget plan touts reduced federal spending, sweeping tax cuts, deregulation and trade realignment as pillars of an agenda that “will set the stage for the next generation of American greatness.”

The USDA said it is eliminating “wasteful spending,” refocusing services on farmers and moving away from programs seen as serving the interests of Washington bureaucrats “who have never set foot in a field or pasture.”

Behind the scenes, Kevin Shea, a longtime USDA stalwart based in Washington, D.C. who retired in January after serving as Deputy Administrator for Policy and Program Development for the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, described a department grappling with low morale and mounting strain.

“There’s simply no way that they can reduce 15,000 positions and not have it felt by farmers and ranchers,” Shea said.

“The real story”

Shea, who served as a senior advisor and transition manager across multiple administrations, called the 15,000 position reduction “tremendous,” noting that many of the losses came from the very offices that serve farmers directly.

“The biggest chunk of (job) cuts comes from the most directly farmer-facing group,” Shea told Farm and Dairy in an interview, referring to the Farm Production and Conservation unit, which houses the Farm Service Agency and the Natural Resources Conservation Service.

“That can’t help but be hard on individual farmers and ranchers,” Shea said.

In addition to the job losses, the 2026 proposed budget predicts further strain for those and other USDA agencies: funding for the FSA would be reduced by $372 million compared to the previous year, while the NRCS would face a staggering $754 million cut.

While the department and administration have emphasized that many employees are leaving voluntarily, Shea said the reality is more complicated, and that most of those leaving likely wouldn’t have done so without the mounting pressure they’ve faced. According to him, that pressure includes subtle intimidation, fears of surveillance and direct signals that jobs may soon be eliminated anyway.

“The real story is they’ve been either intimidated or discouraged and demoralized, or essentially told, ‘Your job’s likely to be eliminated anyway, so just go ahead and leave,’” Shea said.

In addition to the voluntary buyouts, more than 5,000 USDA probationary employees were let go in early February as part of a government-wide mass layoffs, only to later be reinstated by a court order.

In response to a question about the agency’s shrinking workforce, a USDA spokesperson noted that Rollins signed a directive allowing 53 job types to bypass the federal hiring freeze, positions considered essential for protecting public safety, national forests and the country’s food supply.

“President Biden and Secretary Vilsack left USDA in complete disarray, including hiring thousands of employees with no sustainable way to pay them,” the USDA said. “Secretary Rollins is working to reorient the department to be more effective and efficient at serving the American people, including by prioritizing farmers, ranchers, and producers. She will not compromise the critical work of the Department.”

Background

Pressure has been building since Jan. 28, when the Office of Personnel Management emailed federal employees with a deferred resignation offer. Workers were given a choice: stay in their current positions with no guarantee of job security, or leave with a “dignified, fair departure” and receive full benefits and pay through Sept. 30. The first decision window closed on Feb. 12. A second round followed a month later, offering roughly five months’ severance to those who chose to exit.

As of May 1, 15,182 USDA employees had accepted the buyout, according to a department spokesperson.

The shakeup within the USDA and the federal government at large has since collided with several legal challenges. Following a federal court ruling temporarily blocking efforts to fire probationary employees, the USDA was required to reverse course, restoring those employees to paid status, providing back pay and initiating a phased plan to bring them back to work.

The wave of disruption started with Executive Order 14210, issued by Trump on Feb. 11, which launched what the White House called the “Department of Government Efficiency” Workforce Optimization Initiative. The order directed agencies to prepare for sweeping staff reductions, particularly in functions “not mandated by statute or other law,” including diversity, equity and inclusion programs.

In the weeks following the order, Russell Vought, director of the White House’s Office of Management and Budget, and Charles Ezell, acting director of OPM, issued a memo accusing the federal bureaucracy that came before it of funding “unproductive and unnecessary programs” that benefit “radical interest groups” and demanding agencies submit reorganization plans identifying what roles and offices could be eliminated or relocated.

However, those plans were soon met with resistance. In April, a coalition of labor unions, nonprofits and local governments filed a legal challenge, making the argument that such a dismantling violated the Constitution.

U.S. District Judge Susan Illston agreed, and on May 9 issued a temporary restraining order halting further action by the agencies named in the lawsuit — including the USDA — from executing planned layoffs or releasing reorganization blueprints.

In her ruling, Illston wrote, “It is the prerogative of presidents to pursue new policy priorities and to imprint their stamp on the federal government. But to make large-scale overhauls of federal agencies, any president must enlist the help of his co-equal branch and partner, the Congress.”

The restraining order was extended on May 22. It was widely reported that USDA’s was originally expected to be released on May 27.

When asked about the pending litigation, a USDA spokesperson declined to comment, referring all inquiries to the Department of Justice.

Decisions

As the legal battle over the department’s reorganization carries on, the ripple effects continue to be felt by former staffers such as Nicolai Solomon, a remote worker out of Asheville, North Carolina, who once helped champion the department’s public service mission and is now charting a new path forward.

Solomon worked on initiatives supporting local food systems until the Trump administration’s offer to resign his position with full pay and benefits until Sept. 30 led him to leave government and launch his own business aimed at helping nonprofits secure critical funding.

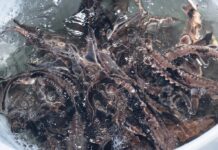

He joined the USDA after serving in the Peace Corps in Zambia, where he supported agriculture programs like fish farming, followed by graduate school in North Carolina.

“And that really got me down the path of giving back, wanting to provide and help people live better lives,” Solomon said.

Since 2022, he was part of the team administering the Local Food for Schools Cooperative Agreement Program and the Local Food Purchase Assistance Cooperative Agreement Program, which supported getting locally grown food into school cafeterias and strengthening regional food supply chains, efforts he described as “something I really wanted to be a part of.”

The programs Solomon worked for were canceled by the administration in March. Seeing the writing on the wall, he opted into the second round of buyouts

For his part, he said his time at USDA helped him understand both the promise and the limitations of government service.

“I think I learned so much from my government experiences. Just getting a little taste of how government works,” he said. “It’s just people making decisions that they think are the best to help other people.”

I enjoy reading your paper – but I am a non-farmer so not familiar with what these agencies do for the farming community. Could someone explain what they do for farmers please. Thank you.

I did plant pathology research work on legumes here in Washington. We test various legumes strains for disease resistance and help farmers by identifying diseases that show up in crops. Before I resigned due to DOGE pressure, I was helping to work on developing ways to identify specific rhizobia that might protect and aid legumes. I was also working on plate assays that might identify beneficial root bacteria that might protect legumes against fungal infections. All that is done now ( literally in the hazardous waste , autoclaved , destroyed) as I was the only scientist with the molecular skills to do the research work. Other scientists at the station were looking at job opportunities in Europe. Bye bye American science!