BURTON, Ohio — Anna Koplik stokes a coal-based fire before pulling out a hot piece of metal. Setting it on an anvil, she slams a hammer into it, again and again and again. The sound reverberates throughout Century Village in Burton, Ohio — a modern-day calling to older times.

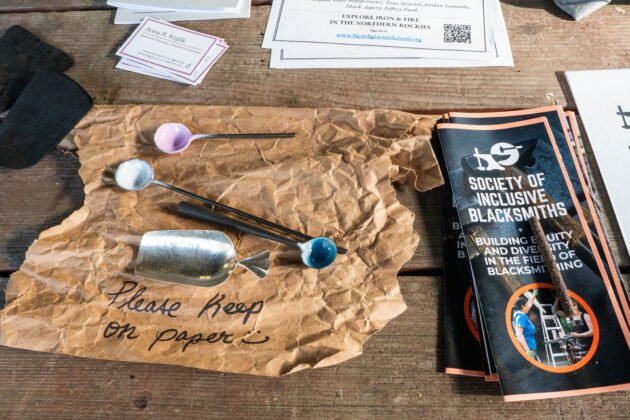

Koplik was the featured blacksmith at the Western Reserve Artists Blacksmith Association’s annual Conference from June 27-29. At the event, blacksmiths gathered around as Koplik demonstrated the art of spatula, hammer and spoon making.

While some outsiders may see blacksmithing as a lost art, the association brings together the region’s best blacksmiths to keep interest ablaze and to light a fire in newcomers.

Whether it’s a railing, a sculpture, a horseshoe or a hammer, handcrafted items matter more than buying a cheap version at the store that’ll break in a year, Koplik said.

“Versus, you meet a person who has been dedicating their life to learning a craft and has put their blood, sweat and tears into making something that’s going to probably last for the rest of your life and might be passed down through the generations,” Koplik said.

Modern-day blacksmithing

Blacksmithing has taken on many forms throughout the centuries. The first recorded instance of blacksmithing can be traced back to the Hittites, an ancient civilization that thrived in modern-day Turkey from 1600 B.C. to 1200 B.C.

The Hittites discovered how to forge iron ore, and when the civilization spread, so did this knowledge.

From there, the trade quickly evolved to making knives, daggers and swords out of iron in the Iron Age, 1200 B.C. to 550 B.C.

During the Middle Ages, which lasted from the fifth century to the 15th century, blacksmiths were reportedly leaders in villages and started making household tools.

From the first time Europeans set foot in America, this country has relied on blacksmiths. Blacksmiths in colonial times didn’t have specialties but made whatever products were needed. Blacksmiths also forged horseshoes and other tools during the American Revolution.

This trend continued until the Industrial Revolution, when machines replaced blacksmiths in the mass production of weapons, household items and other tools.

Blacksmithing didn’t see a resurgence until the 1970s when people had a renewed interest in handmade craftsmanship.

Society wouldn’t be here today without blacksmiths, said Roy Troutman, president of the Western Reserve Artists Blacksmith Association. They were the first ones to heat up iron in coal furnaces to make steel.

“That’s when the big boom happened, when man learned how to make steel, everything evolved from that: buildings, factories, warfare. It all started with blacksmithing,” Troutman said.

While Troutman speaks to the importance of blacksmithing in the past, Koplik looks to its importance in the future.

“It’s going against this consumerism culture where you just get a cheap thing, let it wear out, throw it out,” Koplik said.

Blacksmithing encourages people to reuse their items, says Kopilk. That’s because blacksmiths create a piece that is built to last, and if it does break, it can be repaired by the same person who made it.

“If you’re understanding where the things that you are using came from, it’s going to be better for you. I think it’s better for our world,” Koplik said. “And then you’re also supporting someone who is passionate about what they’re doing, which I think is really important as well.”

Passion is a key element of blacksmithing — that’s what the Western Reserve Artist Blacksmith Association was founded on.

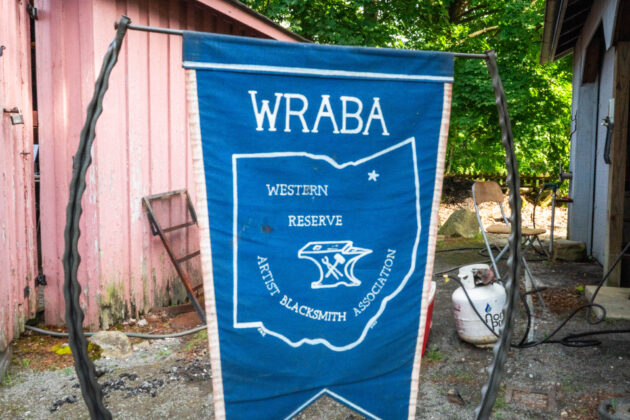

Western Reserve Artist Blacksmith Association

The Western Reserve Artist Blacksmith Association was created in 1987 by the late Art Wolfe, who owned a hardware store in Cleveland, Ohio. When Wolfe first started hosting blacksmith workshops, it was a small gathering of 15 individuals, designed to bring blacksmiths together to learn from each other’s craft.

The group started getting traction in 1997 when the organization became a non-profit and joined the Artists Blacksmiths Association of North America; it reached a peak of 145 members at one point. Today, the group has 60 members.

Troutman, who was a farrier by trade, got involved after he bought horseshoes from Wolfe’s hardware store. With a little experience under his belt forging horseshoes, he joined the association to expand his metalworking skills.

Years later, the association is heavily involved in the local community. It hosts demonstrations at Century Village Museums’ events, including its Apple Butter Festival, Antique Power Show and Civil War Reenactment event.

Western Reserve also puts a particular emphasis on education and bringing in newcomers. Members will go to blacksmith schools across Ohio and Pennsylvania to teach emerging blacksmiths new skills.

The annual conference is another way the Western Reserve Artist Blacksmith Association extends its education. Every year, it features an outside or in-house (club member) demonstrator who specializes in a particular area of blacksmithing.

The purpose of the conference is to learn from other blacksmiths, though it is open to the public.

“People get stale,” Troutman said. “People like to learn different techniques and different ways to stay connected. We all strive for excellence, but I am not the best at what (Koplik) does.”

Anna Koplik

Koplik’s interest in metal started while she was working toward a Bachelor of Fine Arts in jewelry making at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, New York. She discovered the university’s blacksmith shop above the jewelry studio and, after one class, the fire in her ignited.

“At that point, I had already been doing small foraging and sheet metal work in jewelry, and really enjoyed anything with metal smithing that I could do,” Koplik said. “But then I found that there was this whole other thing that was basically nothing but swinging a hammer and more fire.”

Koplik graduated from Pratt Institute in 2015 and went on to hold several seasonal positions working as an assistant and shop technician at Peters Valley School of Craft in New Jersey and Touchstone Center for Crafts in Farmington, Pennsylvania. She would help the blacksmith instructors during the week, and on the evenings and weekends, she would master her own craft.

Eventually, she went on to become a journeyman blacksmith who travels across the county to demonstrate her craft — that’s how she ended up at Western Reserve’s annual conference.

Marc Yanko, a member of the Western Reserve Artist Blacksmith Association and former instructor at Touchstone Center for Crafts, first met Koplik when she was an assistant at Touchstone. He still carries around a bottle opener she made for him back then.

“It’s very, very hard to do what she does, to have the hammer control that she has. A lot of guys just get out there and heat up steel and start pounding on (it) until it takes some kind of shape. But, to know what you’re doing to get a specific shape, it takes a lot of skill,” Yanko said. “That’s one of the advantages of being in the club, is, if you lack a skill of some sort, somebody else is a specialist in it.”

Now that Anna is a journeyman blacksmith, she has demonstrated her specialty of making spatulas, spoons and scoops at conferences across the country.

But getting to this point was a journey in itself. As a woman blacksmith, feeling like she belonged in a space primarily occupied by men wasn’t an easy fit.

“I didn’t have anyone, when I first started, to really look up to. There are other women out there and plenty of different types of people out there doing blacksmithing, but not as many. So you were less likely to run into them just out in the wild,” Koplik said.

It took years for her to finally meet her women blacksmith role models. Despite this, she stayed in the field because of her passion for the work and how welcoming the community is. Now, she aims to create space for female blacksmiths through her work, traveling the country and teaching the art of blacksmithing.

“That’s part of why I also really enjoy teaching and demoing because if I am out there, people see that I am doing this, then other people know there is a space for them in the field,” Koplik said. “I think that makes a huge difference.”

Western Reserve Artist Blacksmith Association hosts an open forge every Tuesday from May 6 to Oct. 25 for those interested in learning the art of blacksmithing. To learn more about the association, visit https://www.wraba.com/. For more information on Anna Koplik, visit https://www.annarkoplik.com/.

(Liz Partsch can be reached at epartsch@farmanddairy.com or 330-337-3419.)