As large game became increasingly scarce with the ongoing expansion of settlements across the Ohio country, pioneers had to rely more and more, for their food, on smaller animals that had managed to adapt to people and civilization.

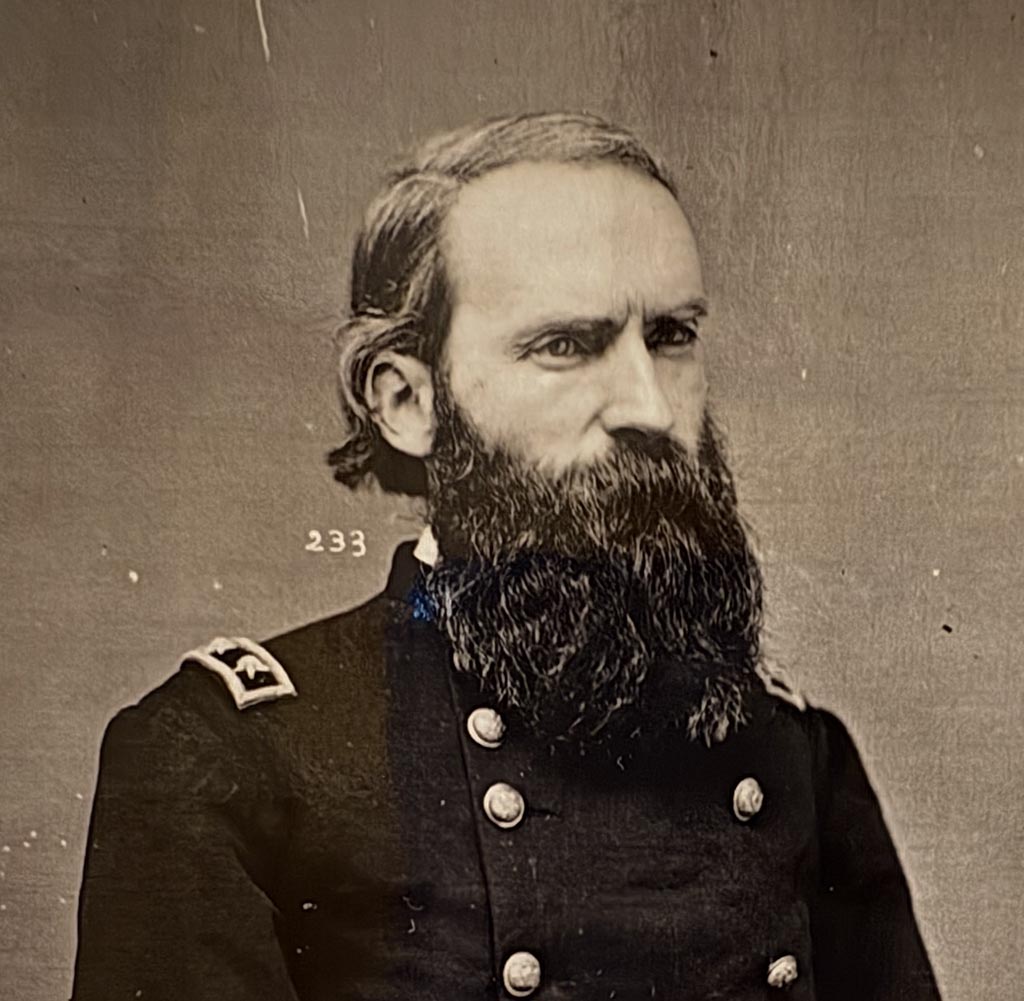

In his memoirs of growing up on the Ohio frontier from 1828 to 1848, published in 1917, Medal of Honor recipient Major General David Sloane Stanley wrote about what it was like to pursue this smaller game as a huntsman. His narratives on this subject are some of the best to survive from the early 19th century.

On hunting raccoons

One of the animals that Stanley most enjoyed pursuing for the family table was the raccoon, of which he wrote: “The ultimate of the hunts was that of the coon. This animal was still quite abundant after I was large enough to follow along in the hunt. The coon could be hunted at any time, except in the cold of winter when they hibernate.”

Stanley characterized the raccoon as “an indefatigable hunter, and soon as night falls he is on the go,” noting, “when the corn comes to the condition of roasting ears, then the coon devotes himself to it, and then the hunter sallies out nightly to protect his corn and to take the coon’s hide. When they are abundant, their ravages in the cornfield surpass the ruin wrought by the squirrels. One coon,” Stanley observed, “will in the course of a night, pull down thirty or forty stalks of corn, only eating part of the soft ears and destroying the remainder.”

The thrill of the hunt, Stanley wrote, was using dogs to run the raccoon — sometimes more than a mile — before it climbed the largest tree it could find. Then the hunters cut the tree down to get to the animal.

Stanley wrote that raccoons “are famous fighters — snarling, yelling, growling, biting and scratching. An old coon will give a large dog a very hard fight. The hunt is very exciting and is a joy of strong boys. I have seen grave and sedate doctors join in the sport with boyish glee.”

As for dining on raccoon, Stanley wrote, “The animal has some value on account of its fur, but as an article of diet, I never could relish coon.”

On hunting groundhogs

Stanley characterized groundhogs as “a marauder, fond of pumpkins, turnips, apples and green corn. Pretty and comic in their looks and motions, they were a nice thing to have on a farm, but they must feed.” He wrote that because the settlers were determined to hunt the groundhog to extinction like they did the elk, bison and deer, there were “men fifty years of age in the old neighborhood (that) have never seen a woodchuck.”

He said that the dogs used in hunting the groundhogs “used to dig them out of their burrows, or sometimes catch them under the puncheon floor of the old barn. They, too, were fighters, and their great chisel-like teeth would cut a dog severely. I remember on one occasion we found a large specimen of this animal under our barn floor. We called our great big black dog Tim, a huge mastiff-built animal. He crept under the barn floor, cornered the groundhog, and pulled him out into the daylight and dispatched him.”

On hunting weasels

Stanley recalled in his memoirs that “The mink, the polecat and the weasel were denizens of this new country and often carried their forays into our hen house. We waged war against these small pests, but they were very hard to catch.” He particularly recalled “a young woman … coming through the woods to our house who saw a weasel run into a hollow log. She broke off some dead limbs and stopped the hole in the log, and told us of the place. Taking an axe with us,” Stanley continued, “we soon cut a hole in the log and pulled the weasel out, taking care to rap his head with a stout stick to evade his sharp teeth. The fellow squealed fiercely, snapped his teeth and emitted a strong odor that was anything but pleasant.”