Some natural phenomena are difficult to study and understand because they occur occasionally, ephemerally and unpredictably. Late summer swarms of dragonflies fall into this category.

Over the last several weeks I’ve received many emails and letters from readers reporting large aggregation of dragonflies, usually hovering above the grass in wet meadows and hayfields. The last time readers reported such swarms was in 1993, when many described “clouds of dragonflies that darkened the sky.”

Helpful predators

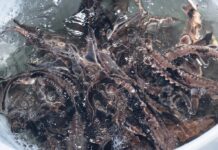

Though dragonflies are predators and have a ferocious appearance when viewed up close, they are harmless to people. They do not sting, but they are serious predators of flying insects such as mosquitos, gnats and midges. So dragonflies are great to have around.

Their mouth parts are designed for biting and chewing, so larger species can pinch human flesh but they can’t break the skin. Furthermore, you’d have to catch and hold a dragonfly for it to have a chance to pinch, and that is much easier said than done.

Entomologists offer several explanations for late summer swarms of dragonflies. John Rawlins, curator of invertebrate zoology at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History, and Rosser Garrison, senior insect biosystematist at the California Department of Food and Agriculture agree that there may be several explanations.

Reasons

The most obvious explanation is that swarms are groups of migrating dragonflies. Some dragonflies do migrate, and the timing is right. But migrating dragonflies, particularly green darners, are most often seen at high elevation hawk-watching sites such as Hawk Mountain in eastern Pennsylvania.

Rawlins suggests that populations of migrating dragonflies might explode occasionally as an “ecological escape” from overpopulation.

“Perhaps dragonflies themselves occasionally experience a population explosion,” Rawlins explains, “that makes their late summer migratory swarms almost impossible to miss.”

Garrison suggests another explanation of late summer swarms of dragonflies hovering just above grassy vegetation is that they are preying on clouds of mosquitos, gnats and midges.

In such cases, the tiny flies would be invisible to the distant naked eye, and it would seem that the dragonflies appear for no reason. But they are enjoying a feeding frenzy. When the prey species disappears, so do the dragonflies.

Regardless of the explanation, keep your eyes open over the next few weeks. You might see evidence that this has become a “summer of the dragonfly.”

* * *

Back in June, I bought a 50-pound bag of black oil sunflower seed and was shocked when the cash register rang up $35. I paid as little as $11.99 for the same bag a year ago, though I usually pay between $15 and $20 for 50 pounds of black oil seeds.

Factors

I wanted to understand the significant price hike, so I made some phone calls. I got several explanations, but none from anyone willing to go on the record. Obviously, gas and diesel prices have risen steadily the last few years, so transportation costs via rail and truck are up.

This spring’s wet weather in the Great Plains may have delayed planting of this year’s crop. How much actually matures by harvest time depends on fall weather, so market uncertainty is a factor.

Another factor is that less sunflower acreage may have been planted this year. Wheat, millet, corn or soybeans may have been a better bet.

Finally, one brave source suggested that farmers or middlemen may be manipulating the market. Sunflower seed can be stored in silos for two years or more. As long as it stays dry, it does not deteriorate. Farmers may have been holding back seed since last fall to drive the price up.

That’s the bad news. The good news is that as the fall crop is harvested, farmers need a place to store it. So they’ll be selling what they’ve been storing to make room for the new crop.

As the supply of sunflower seed recovers, I’m hoping sunflower seed prices come down by Thanksgiving. If they do not, I’ll be stocking up on seed every time I see a big sale.

Where are all the juncos? I have not seen one this winter.

Penn Hills

I know this is a very old story but I am noticing in north central WV that we have a lot of dragonflies, even in the city where there is no water. Why could that be? Thank you in advance for your answer

I have owed 3arces of my dad’s farm now for 20 popyrs. I have never seen this many dragon flies here like I am now. There are swarms of them all over my yard

I live n swamp east Missouri, as I call it cause It is low lying ground. I’m surranded by crops except for one side that is woods.

We had a lot of rain last yr all year long.

Very glad to hear they eat mosquitos, because we have lot of those too.

Thanks for explaining this to me. Gala Deckard