June 20, the longest day of the year, is also known as the summer solstice. This day is the official start of summer in the Northern Hemisphere, and as if on cue, ushered in the hottest days of the year last week. Most of Ohio recorded temperatures well into the 90s with high humidity.

Researchers from Poland recently published a study in the scientific journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that provided a fresh insight between trees and summer solstice. They discovered regardless of where in Europe beech trees lived, they opened a temperature-sensing window on the solstice, using it to decide how many seeds to manufacture the following year. If it is warm on the days immediately after the solstice, they will produce more flower buds the following spring, leading to a bumper crop of nuts in the fall. The research showed if the weather is cool they might produce none, a phenomenon known as masting.

The window of temperature sensitivity opens at the solstice and provides the beech trees with a strategy for next year’s growth and production. Further research from the University of British Columbia (Meersch, Wolkovich) suggests that trees reach their thermal optimum — the temperature range where their physiological processes are most efficient — around the summer solstice. This was surprising because the warmest days are usually in July or August, not around the summer solstice. This time-sensitive window can provide cues for the trees to hold onto their leaves longer in the fall for optimum photosynthesis or to accelerate the aging of their leaves.

What’s that got to do with bees? Bees rely on the trees and other grasses and shrubs to provide them with the nectar and pollen to survive.

This research highlights the correlation between weather conditions and key factors that will play a dominant role in how well trees and plants produce flowers next year. Even if you have a bumper crop of forage for the bees next year, the weather has to be optimum for the bees to be able to get out and harvest it. Inclement conditions when the bloom occurs can reduce forage time and result in little or no production from important sources of trees. I believe this year, the steady successive rains drastically reduced the important honey locust flow bees harvest in early spring.

Beating the heat

Almost everyone, especially the bees, will choose summer as their favorite season. Longer daylight, crops growing, flowers blooming — what’s not to like? Most of us can retreat to the cooler house when the temperatures spike, but what do the bees do? They simply turn on their portal fans and direct the airflow into the hive to cool things off.

To optimize the cooling effect through evaporation, foragers will start to bring in water that will be deposited within the inner walls of the hives. The temperature inside the hive is regulated by the bees by fanning and also clustering outside the box to reduce the occupancy and allow better air flow. The brood on the frames must not get overheated and must be maintained between 94 to 97 degrees.

During periods of high temperatures and high humidity, the bees will self-regulate the hive temperature by adjusting the numbers and positions of bees on the exterior of the hive entrance. You can help the bees by having an available water source nearby so they don’t have to fly a distance to forage for water. This is also advisable because they may find your neighbor’s swimming pool and this becomes a source for another article.

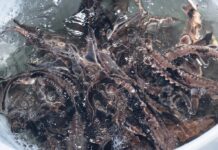

Many beekeepers simply use a five-gallon bucket of water that either has blocks of wood or other floatation devices for the bees to land on. A piece of burlap bag draped over the bucket sides and into the water makes a great waterer as the burlap wicks up the water and the bees will land on the wet burlap to drink.

You will be surprised how much water the bees can take down on a hot day. Some studies have shown large hives can take up to a quart of water for cooling and brood production. If you want to get fancy, pick up a $9.99 submersible fountain pump from Harbor Freight. Find an old, cheap galvanized or plastic bucket from a garage sale or auction and make yourself a bee bubbler. Position the pump in the bucket, add some landing rocks and you have a continuous summer splash pad for your bees.

The downside is you have to be close to an electric outlet, but you’ll be surprised to see how many other winged, hooved and five-fingered critters will be attracted and appreciate your fresh cooling water fountain on a hot August day.