SALEM, Ohio — Paul Harvey lived a full life, wearing many hats in his 80 years in Coolspring, Pennsylvania, where he spent most of his life in the house he grew up in.

He was a boy practicing his trumpet on his front porch — much to his neighbor’s dismay. He was a college kid selling Compton’s Encyclopedias door to door. He was an avid collector of early gas engines in western Pennsylvania. He was a doctor at DuBois and Brookville hospitals and Allegheny Health Center for 50 years — and a doctor who would accept same-day house calls from the residents of Coolspring.

He was the owner of Coolspring General Store because he wanted to preserve it for as long as possible. He was a co-founder and permanent board member of Coolspring Power Museum. He was a member of Coolspring Presbyterian Church, where he was an elder and a Sunday school teacher. He was a son, husband, father, grandfather and friend.

“He was one of us. He was special,” said Lorraine Hilliard, a Coolspring resident, former general store employee and longtime friend of Harvey.

Harvey was easily recognized around Coolspring, driving his green John Deere Gator and smoking his pipe. So naturally, he was buried with his pipe and a pouch of tobacco tucked into the pocket of his red plaid flannel shirt, following his death Feb. 19 at Penn Highlands DuBois.

Harvey was also well-known among antique engine collectors all over North America, and it’s no surprise. He was known for “dragging them out of the woods on old trucks and trailers,” Harvey’s close friend Tom Rapp said.

Harvey was always searching for his next great find — a passion that started when he was a sophomore in high school and led to the inception of Coolspring Power Museum.

Getting started

College was the only time Harvey lived outside of Coolspring. After commuting to Clarion State College for a year and deciding to study medicine, Harvey moved away to attend St. Vincent College in Latrobe, Pennsylvania. Then, after graduating in 1965, he attended the West Virginia University School of Medicine.

While he inched closer to his medical degree, he opened a new world, exploring a large oil field on the eastern border of Morgantown, West Virginia. With any time off, Harvey took his International Harvester C series pickup truck and explored.

Harvey had been collecting small engines with his father, a mechanic, for nearly 10 years when he met John Wilcox, the other co-founder of CPM, at the Rough and Tumble steam and gas engine show during the summer of 1967, in Kinzers, Pennsylvania.

Harvey struck a deal to buy a small Model 4 Klein engine from Wilcox to add to his collection before the 12-by-20-foot engine house he was building with his father was finished. The day Wilcox dropped off Harvey’s purchase, they decided to explore a nearby oil field and found a vertical Klein that Harvey purchased for $15 and later displayed in the engine house, which is today called the “Founders Engine House.”

As his collection grew, Harvey was just getting started in his career. After completing an internship at Washington Hospital in Washington, Pennsylvania, and passing his board exams, he set up a medical practice in Brookville, Pennsylvania in July 1970. However, he only stayed in private practice for four years before he became an employee of Brookville Hospital and directed their emergency department for the next 36 years.

“He really did have a big heart, and he really cared about his patients more than the average doctor. It was really amazing. He started out having a private practice, and that failed miserably because he was in a fairly poor area up there and his patients wouldn’t pay him. He would never go after them for the money, ever. (He) never even consider it,” said Clark Colby, Harvey’s longtime friend.

Even after Harvey started working at the hospital, he never turned away a resident of Coolspring who showed up at his house needing help.

Sharing his wealth

Harvey’s generosity toward his neighbors didn’t stop at his medical practice. He purchased Coolspring General Store two different times from 1977 to about 2009 to preserve its history and maintain a meeting place for the community. In between, he sold it to Hilliard, who owned it from about 1980 to 1993 and worked there as an employee for the duration of Harvey’s ownership both times.

Harvey never made money owning the store. Sometimes he lost money — his idea to sell penny candy at two pieces for a penny wasn’t lucrative, and he couldn’t have been making out on the fabled 9-ounce ham and cheese sandwiches he sold at the store. Owning the store, like so many other endeavors, wasn’t about making money for Harvey.

“He bought the store to preserve the oldness of it,” Hilliard said.

When Harvey owned the store, he fixed it up the way it had been when he was growing up. He oiled the wood floor annually. He repaired the big pot-belly stove that heated it, having a new bowl cast for the bottom.

Walking through the front door, customers were welcomed by the large pot-bellied stove directly ahead. On either side of the stove, sat wooden benches where customers would sit and share town news. To the right, the penny candy counter featured old glass countertops and glass jars filled with candies. To the left, the post office rented space.

“Coolspring is a very small town, and so it was a local gathering place for people,” Hilliard said.

And when the store wasn’t doing well, he paid his employees out of his own pocket.

“He was the best of doctors that ever there could be. He was the best of friends that ever could be,” Hilliard said.

Building a private collection

During his private practice years, Harvey and Wilcox expanded the engine house to 24 by 20 feet in 1971 and, finally, 24 by 56 feet in 1973 to house their rapidly growing collection. They also added structures as pipeline companies downsized and modernized, selling gas engines for junk price at $18 a ton. In 1971, the Big Barn — or what is known as the Power Technology Building today — was constructed. Two years later, the Power House, which would later be renamed the John P. Wilcox Power House, was built. The Machine Works was constructed in 1974, and in 1975, Harvey and Wilcox acquired McKee Station, a National Transit Pipeline Station located south of Clintonville, Pennsylvania. They moved the entire building, stored it through the winter and re-erected it the following year.

“He was well enough known by the bookkeeper at National Transit that he’d call up this guy and give him a serial number off this engine that was abandoned in place. And the guy’d say, ‘OK get it out, and when you get it out, give me another phone call and send me a check for $50, and I’ll take it off the books,’” Colby said.

Many of the engines Harvey and Wilcox salvaged and relocated to Coolspring had escaped scrap drives through two world wars and sat abandoned, ripe for the picking. Their collection grew quickly, and other collectors came from miles around to see it.

“It became one of the better places to go to see privately-run engines,” said Coolspring Power Museum President Mike Murphy. “And then, as this grew and grew, they decided, OK, we need to make this something more official. This collection is really unique in the world, and it really has some spectacular items in it.”

As their collection grew too unwieldy for two people to maintain, Harvey and Wilcox decided to form a museum in 1985, with the help of friends who attended their engine runs to ensure the future of their collection. When the museum was formed, Harvey owned over half the engines in the collection.

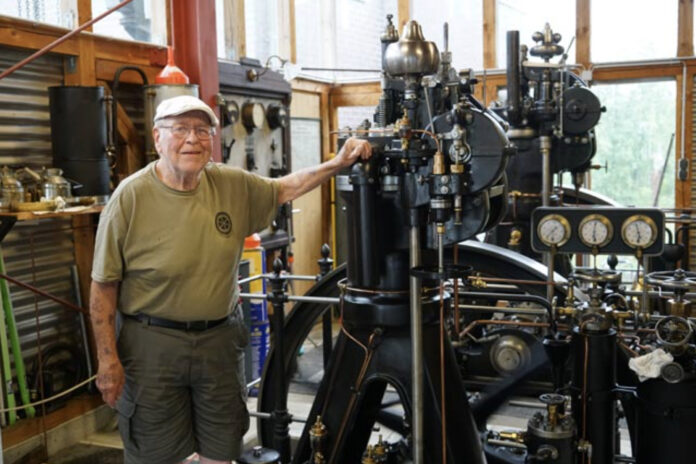

Today, CPM features over 275 engines — many of which are permanently mounted and operational — housed in 35 buildings and outdoor displays. The American Society of Mechanical Engineers designated the museum as a Mechanical Engineering Heritage Collection in 2001 and presented it with a plaque that states, “This is the largest collection of historically significant stationary internal combustion engines in the United States.”

“He put all of his money into that collection and the museum. He was willing to overpay a little bit for engines that he thought were historically significant, and it turned out to be the exactly right thing to do,” Colby said.

One of a kind

Harvey was primarily responsible for bringing dozens of large displays into preservation at CPM, including McKee Station, Windy City Air Plant and its 300-horsepower Miller engine. However, the crown jewel among his acquisitions is a 175-horsepower Otto engine with 10-foot flywheels that once powered the Water Works in nearby Brookville, Pennsylvania.

Wilcox originally purchased the 25-ton engine and 20-ton Deane pump for $1. Then, he spent most of 1969 dismantling them and hauling the parts — except for the engine’s main frame, which required special trucking — to his home near Columbus, Ohio. However, he never got it re-erected, and when his health started failing 35 years later, he sold it to Harvey who moved it to CPM.

The Otto engine was one of only five built and possibly the only one left in existence. It’s one of the largest single-cylinder gas engines in the world. It is currently reassembled, in running condition and on display in CPM’s Power Technology Building, sitting on a 20-by-10-foot foundation, roughly 9 miles from where it worked its entire life.

Preserving history

While Harvey’s collection is the foundation CPM has built off of for the last 40 years, it’s far from his only contribution to the displays there.

Harvey took a special interest in the Pennsylvania oil field and obtained a lot of engines that were built locally. He spent considerable time researching their history in Butler, Erie, Franklin, Pittsburgh and Oil City to make display plaques for each one for the museum, as well as to write articles about their history for Gas Engine Magazine; CPM’s monthly online publication, The Flywheel; Bores & Strokes, another CPM publication, and several local newspapers.

He spent days tracking down information on these engines, working with historical societies and combing through microfilm of small-town newspapers.

In some cases, he and Wilcox were even fortunate enough to hear the history of the acquisitions firsthand.

“John and Paul were early enough into the collecting days that a lot of these very old timers that were still working in the late ‘50s, early ‘60s, they were able to regale John and Paul with some of the actual stories of using this equipment and dealing with this equipment,” Murphy said.

Lifelong treasure hunt

For the most part, Harvey was driven by his passion for preserving the history of Coolspring and the rich engineering feats in oil and natural gas fields, hotels, trolley stations, utilities and farms across western Pennsylvania. But he also enjoyed trips across the United States and Europe in search of unique engines.

“I can’t tell you how many tens of thousands of miles we put on (vehicles) driving across this country. I mean, I’ve been to 48 of the 50 states with him,” Rapp said.

Rapp and Harvey trekked across the country and beyond for over 30 years, chasing antique internal combustion engines and steam engines. One of their last acquisitions was the Graz Diesel — the oldest operational Austrian-built air blast diesel in the world. The engine was offered to CPM following a trip to the city of Hof in Bavaria, Germany, in 2019, to learn how to operate CPM’s Augsburg air-blast diesel engine from an expert. Upon completion, the Augsburg will be the oldest operating diesel engine in existence. Both engines are being reassembled in the museum’s new Diesel Centrale CPM building.

“He was still very much involved up until the end,” Rapp said.

One of Rapp’s favorite trips with Harvey was to Stirling, Scotland where Harvey tracked his lineage to a cemetery near Stirling Castle. They also visited Yellowstone National Park five times together. Rapp recalls the trips being both enjoyable and educational, noting Harvey’s uncanny ability to “always find something out there that was weird and unusual,” Rapp said.

“He was like my second father when my dad passed. And, you know, if you had a question, he was the guy you went to,” Rapp said.

Their last trip together was to Paradise, Pennsylvania, to take pictures for the last column Harvey submitted to Farm and Dairy, which he fittingly signed off, “From Paradise, Paul.”

Harvey led an interesting life with a unique interest he followed near and far. In some ways, he lived his life in a time capsule, surrounded by the belongings of generations of his family in his childhood home and surrounded by generations of antique internal combustion engines at CPM. His friends joked about what patients may have thought when he went to work at the hospital on Mondays with grease on his hands. But people come from all over the world to experience the collection he helped put together on what used to be his family’s farm.

“He would have never fit into big city life, but he fit right at Coolspring,” Colby said.

•••

Funeral services for Harvey were held Feb. 27 and officiated by the Rev. Robert Hrisak at Shumaker Funeral Home, Inc. in Punxsutawney. Harvey was laid to rest at Ohl Cemetery.

Memorial donations may be made in Paul’s memory to the Coolspring Power Museum, 179 Coolspring Road, Coolspring, Pennsylvania 15730.