CHESWICK, Pa. — Medicaid is more than just healthcare coverage; it keeps “fragile” rural health systems afloat, according to Lisa Davis, director of the Pennsylvania Office of Rural Health.

But now, thousands of people across Pennsylvania, Ohio and West Virginia could lose coverage after the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act,” H.R. 1, was signed into law by President Donald Trump on July 4.

The bill cuts federal spending on a number of things, including Medicaid, which covers over a quarter of rural residents in the United States.

But even those who aren’t covered by Medicaid will see changes, says Davis, who is also an associate professor at Penn State University’s College of Health and Human Development.

The largest impact from Medicaid cuts will be on rural hospitals, she says, as they rely heavily on Medicaid funding to keep operations afloat.

Without this funding, these hospitals and rural health clinics could cut critical services like maternity wards and in-home care or, worse, close altogether, leaving residents to travel farther distances for life-saving care.

“Medicaid cuts will impact essentially everybody in one way or another, either directly or indirectly,” Davis said.

Changes to Medicaid

Medicaid is a joint federal and state government program in the United States that provides medical and health-related services to low-income people. It was created by President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1965, and qualifying people included adults with disabilities, low-income parents with dependent children and pregnant women.

The program was expanded in 2014 to include adults with a household income of 138% below the federal poverty level. For a household of one, this would be an annual income of $21,597.

According to Davis, changes to Medicaid through the Big Beautiful Bill will mostly target the population that received Medicaid through this expansion due to a loss of federal funding and new work requirements.

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act will gradually cut federal funding for Medicaid by $1 trillion over the next 10 years. Pennsylvania will lose more than $39 billion in Medicaid funding, something that Pennsylvania Gov. Josh Shapiro says the state can not backfill.

Starting in January 2027, the bill also sets work requirements for able-bodied Medicaid recipients between the ages of 19 and 64. This includes completing 80 hours of work or community engagement per month or 20 hours of work or community engagement per week to remain eligible.

Many Republicans say the bill’s intent, including the work requirements, is to go after waste, fraud and abuse in the program. That message was echoed earlier this month when Ohio Attorney General Dave Yost filed indictments against nine Medicaid providers for stealing a combined $1.2 million from the program.

“Medicaid fraud is both a crime and a moral offense. It steals from the vulnerable and undermines our values as a society,” Yost said in a statement on July 10.

Who will be impacted?

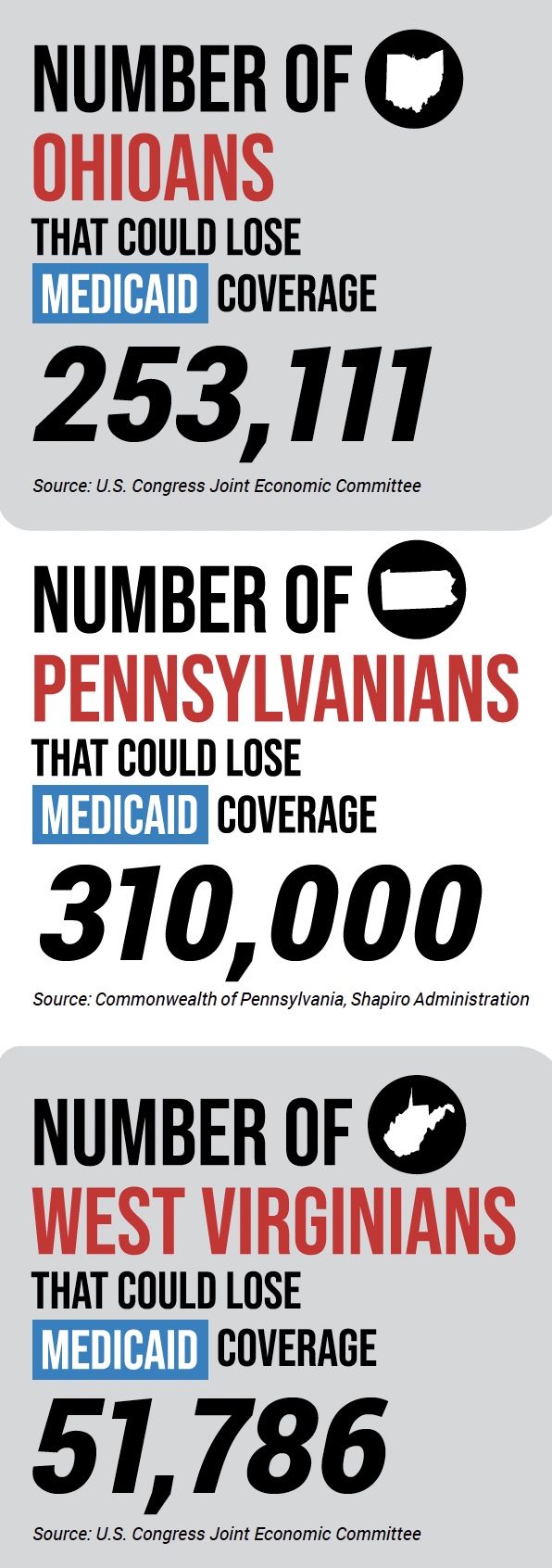

Because of these changes, 310,000 people in Pennsylvania could lose their Medicaid coverage, which covers one in four people in the state, according to Shapiro.

In Ohio, 253,111 people could lose Medicaid coverage, and in West Virginia, 51,786 stand to lose insurance, reports the U.S. Congress Joint Economic Committee.

Rural populations, in particular, stand to be significantly impacted as one in four adults in rural areas rely on Medicaid for health coverage, reports KFF, a non-profit organization focusing on health policy and research.

Rural residents who aren’t covered by Medicaid will also be impacted, says Davis, whose job at the Pennsylvania Office of Rural Health focuses on increasing rural residents’ access to healthcare and working closely with the state’s smallest rural hospitals.

Rural hospitals

With limited funding, rural hospitals — hospitals not located within a metropolitan area — will have few options, many of which have “traditionally been on the edge financially,” Davis said.

Rural hospitals rely heavily on Medicaid and Medicare reimbursements while struggling to make ends meet. Roughly 25 rural hospitals in Pennsylvania are operating at a deficit where more than 50% of their revenue each year is coming from Medicaid, said Shapiro at a July press conference.

In Ohio, hospitals are also struggling to break even, according to a letter the Ohio Hospital Association sent to the Ohio Senate Medicaid Committee in May. “More than 50% of Ohio hospitals (and 72% of rural hospitals) report(ed) negative operating margins over the past few years. The median hospital operating margin was 0.0% in 2024, -0.7% in 2023 and -2.8% in 2022,” the letter stated.

Many of these hospitals also have to provide healthcare to uninsured patients, which is costly, especially for rural hospitals that are already struggling, Davis said.

“The way that this affects rural communities, overall, is that if small rural hospitals begin to see higher numbers of individuals who are uninsured and they need to provide uncompensated care, we’re looking at the potential of hospital closures,” she said.

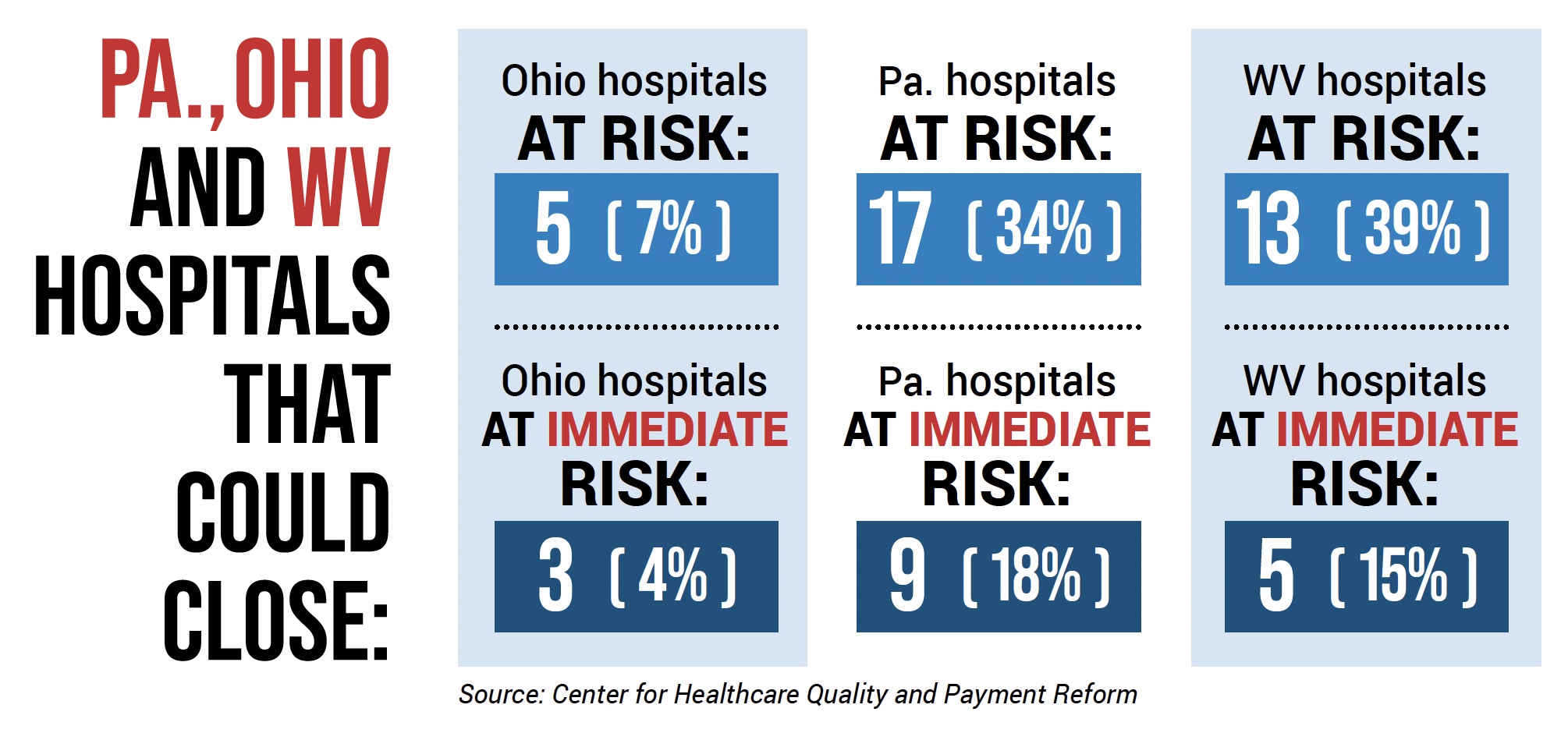

Already, nine rural hospitals, most of which are in western Pennsylvania, are at risk of immediately closing as a result of Medicaid cuts, including four University of Pittsburgh Medical Center hospitals — UPMC Jameson, UMPC Northwest, UMPC Kane and UMPC Horizon — and Penn Highlands Connellsville.

In total, 17 Pennsylvania hospitals could close due to Medicaid cuts, according to the Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform. In Ohio, five hospitals are at risk of closing, and three hospitals are at immediate risk of closing.

Already, Pennsylvania has seen two hospitals close this year. Crozer-Chester Medical Center in Delaware County closed its doors in April, and on June 30, Heritage Valley Health System’s Kennedy Hospital in Allegheny County closed, citing financial problems.

Labor units could close

The loss of Medicaid funding could also result in hospitals closing certain departments. Labor and delivery units, in particular, could close if Medicaid recipients become uninsured. That’s because 34% of births in Pennsylvania were covered by Medicaid in 2023, according to state numbers from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

“Labor and delivery is the most expensive service that a hospital provides,” Davis said.

Rural hospitals need 200 births per year to keep these units financially viable, according to a 2022 survey conducted by the University of Minnesota Rural Health Research Center that polled 300 rural hospitals. At the time, over 40% of hospitals said they had fewer births than what was needed to sustain operations.

Some rural hospitals in Pennsylvania have already had to close. In April, UMPC Cole in Potter County, Pennsylvania, closed its maternity ward. Now, the closest maternity ward is UMPC Wellsboro, which is 50 minutes away from Potter County and serves seven other counties.

“We now have a seven-county-wide maternity care desert that’s roughly the size of Connecticut,” said Erin Gabriel, government affairs representative for the Pennsylvania Health Access Network. For women in labor who live in one of these seven counties, it could take hours of travel to get to a maternity ward, she said.

Homecare services at risk

Alongside hospitals, home care patients — like elderly and disabled individuals — could also lose their services due to a lack of funding. Gabriel is familiar with the benefits of in-home care; she has three children with disabilities and a mother with Alzheimer’s, all of whom rely on Medicaid and two that use it for home care services.

Gabriel said the first health care services to be cut when finances are tight are often home care services.

She is particularly concerned about her daughter Abby, who is autistic, deaf, blind and non-speaking, and uses a wheelchair. Doctors initially didn’t believe she would outlive her parents.

“Abby is, in many ways, a story of everything that can go right with our healthcare system,” Gabriel said. She explained that because of Pennsylvania’s required newborn screening tests, Abby’s hearing loss was found at birth, and she was able to qualify for the home and community-based Medicaid waiver.

Without Medicaid, the support Abby received wouldn’t have been possible, which includes physical, occupational, speech, feeding, vision and hearing therapies.

If Abby’s home care services are cut, she would have to be institutionalized, separated from her parents, siblings and friends, Gabriel said. Gabriel’s elderly mother could also be sent to a nursing home.

“Behind these numbers (of people insured by Medicaid) are real people,” Gabriel said, at a press conference hosted by Pennsylvania Congressman Chris Deluzio, a Democrat representing Pennsylvania’s 17th congressional district, on July 10 in front of Hamar Village Care Center in Chewsick, Pennsylvania.

With Medicaid, “Seniors like my parents can age in place with the people they love, and people with disabilities can participate in their communities and live their lives just like every other American,” she said. “Ultimately, Medicaid means that families like mine can stay together.”

At the conference, which brought together government leaders, healthcare workers and mothers of Medicaid beneficiaries, Deluzio echoed these concerns, stating the Big Beautiful Bill will “make things worse for families all over western Pennsylvania and all over this country.”

Is it enough?

Rural communities could get some funding from the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, which created the Rural Health Transformation Plan. Through the program, Congress has allocated $50 billion to improve healthcare in rural areas from fiscal years 2026 through 2030. That is $10 billion per fiscal year, with $5 billion divided equally among eligible states and the other $5 billion distributed by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to states based on certain criteria.

In order for states to be eligible for the program, they must submit a detailed rural health transformation plan that consists of: improving access to hospitals or other health care providers and services for rural residents of the state, improving health care outcomes of rural residents, prioritizing the use of emerging technologies that assist with prevention and chronic disease management, strengthening and initiating partnerships between rural hospitals and health care provides and more.

Dr. Mehmet Oz, administrator for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, recently announced that applications for the program will be sent out to states in “early September.”

Some praised the funding, including the CEOs of several rural Ohio health systems in a letter to Sen. Jon Husted (R-Ohio) and Sen. Bernie Moreno (R-Ohio), which thanked them for their effort in securing roughly $1.3 billion in funding for Ohio’s rural hospitals over the next five years.

Others say this funding may not be enough. Over half of the Medicaid funding cuts in rural areas are among 12 states, including Pennsylvania and Ohio, which will see a decline in funding of $5 billion or more over the next 10 years, reports KFF.

Davis says that this funding won’t necessarily go to rural hospitals or help uninsured individuals, as the state dictates where this money goes. But it will reimagine rural healthcare, she adds, and just how is still unclear.

(Liz Partsch can be reached at epartsch@farmanddairy.com or 330-337-3419.)

Lots of “coulds” and “mights” in this article, but little to no hard numbers and facts. As for the “able-bodied” having to work some or lose their benefits, so what? The full time worker either has insurance via their employer or pays it themselves. This looks more like another F&D political rant than a factual article, and readers deserve more.