SALEM, Ohio — Hunters may face a different deer season this year after thousands of deer in southeast Ohio have fallen sick or died, reports the Ohio Department of Natural Resources’ Division of Wildlife.

The culprit is Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease, a disease transmitted by infected midges that damages deer’s blood vessels and causes internal hemorrhaging.

According to Clint McCoy, wildlife biologist at ODNR’s Division of Wildlife, there is no way to get rid of EHD once it arrives.

“As EHD becomes endemic to the region, we will expect to see some level of EHD annually,” McCoy said, during a webinar hosted Sept. 9 by the Ohio Department of Natural Resources Division of Wildlife. “Some years are pretty mild, but we’re typically confirming disease in at least a handful of counties every year.”

But this year has been the most significant outbreak the ODNR has logged to date, McCoy said.

EHD

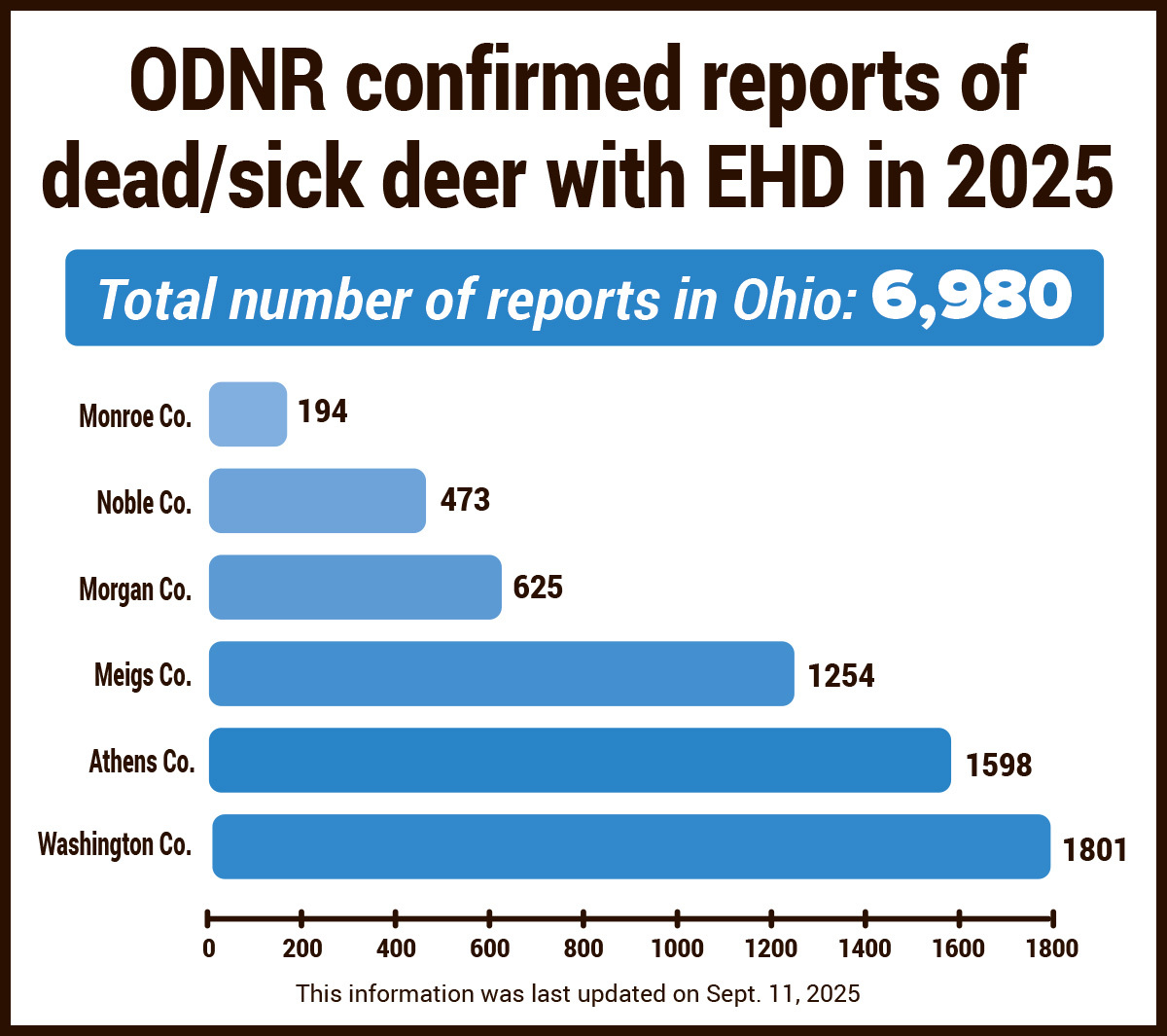

As of Sept. 11, ODNR has confirmed 6,980 sick or dead deer from EHD across 22 Ohio counties. The outbreak is largely concentrated in Athens, Washington, Meigs and southern Morgan counties.

The first significant EHD outbreak in the state was in southeast Ohio in the early 2000s, said McCoy. Subsequent disease outbreaks occurred in 2007, 2012 and 2017.

According to McCoy, the prevalence of EHD in Ohio varies from year to year. In 2022, ODNR confirmed the disease in 47 out of Ohio’s 88 counties — a record for the number of counties, he said— while the following year, the state confirmed EHD in no counties.

The severity of the disease is determined by the prevalence of midges, as infected midges transmit the disease to deer after biting them. The disease is carried seasonally, occurring in late summer and early fall, before winter’s frost kills the midges.

There are several environmental factors that increase midge populations. This includes warmer spring temperatures (which allow midges to breed sooner), higher than average precipitation in July and drought conditions in August, said McCoy, citing soon-to-be published research.

Midges breed in moist and muddy areas near water sources, typically “low-quality water sources,” said McCoy. Because of this, heavy rainfall in July creates more breeding habitats for midges and drought in August enables more breeding in concentrated areas while forcing deer to look for any available water source — even if this water is infested with midges.

“If we look at these three factors that influence the occurrence of hemorrhagic disease, the stars aligned this year to produce the situation that we’re seeing,” McCoy said.

In Washington County, residents saw 6.25 inches of rain in July, 2 inches higher than the state’s average. In August, the county had only 1.35 inches of rain, less than the state’s average by almost three inches, according to data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Center for Environmental Information.

The bright side?

EHD is the most common disease in white-tailed deer in the United States, McCoy said. Deer that contract the disease typically exhibit symptoms within five to 10 days of exposure. Symptoms include respiratory distress and swelling of the head, neck, tongue or eyelids caused by a high fever.

Because of these fevers, deer will often show no sign of fear when faced with humans, said McCoy. Death from EHD usually occurs within two days of symptoms and dead deer are often found near water sources, as they seek water to cool off from the fever induced by the disease.

EHD cannot be transmitted to humans. Livestock can contract the disease, but symptoms are often mild.

EHD can’t be prevented, but there are ways to reduce its impacts through habitat maintenance. According to McCoy, folks can clear shallow, murky and muddy areas, ideal midge breeding spots, and replace them with healthier water sources.

This could entail draining standing water and muddy areas and/or improving water quality and building a wildlife watering hole that’s deep with rocky, vegetated banks.

Although the EHD outbreak will impact deer populations for the time being, McCoy says the population should rebound within three to four years.

He adds deer should become resistant to EHD as they continue to be exposed to it, as is the case for many deer populations in the southern half of the U.S. After decades of exposure, southern deer populations have developed antibodies, making them more immune to the disease.

“(We) look forward to that population rebounding and seeing the fruits of what happens when deer condition gets maximized,” McCoy said.

Pennsylvania EHD

The Pennsylvania Game Commission has also confirmed several cases of EHD in western Pennsylvania. As of Sept. 9, EHD has been found in Butler, Erie, Lawrence and Mercer counties. EHD test results are still pending in southwestern and southeastern Pennsylvania, reports the agency.

According to Travis Lau, spokesman for the Pennsylvania Game Commission, the impact of EHD in Pennsylvania is more localized to certain townships, rather than county-wide. Currently, there is no proof yet of a significant impact across the state, he said.

Because of this, Lau said there are no plans for hunting restrictions. He notes, however, that until EHD season is over — when the first frost hits — Pennsylvania will continue to see new cases in new areas.

Residents in Ohio and Pennsylvania are encouraged to report sick-looking deer. To report a sick or dead deer in Pennsylvania, contact the Pennsylvania Game Commission at 1-833-PGC-WILD (1-833-742-9453). To report a sick or dead deer in Ohio, contact ODNR at 1-800-WILDLIFE (800-945-3543).

(Liz Partsch can be reached at epartsch@farmanddairy.com or 330-337-3419.)