Those who remember the pastures and hay fields that once occupied much of Ohio’s landscape will recall the common, plank-sided barns that were the predecessors of the sterile, steel-encased pole-built varieties.

A walk inside those century-old structures offers a history of rural living and the scents of stored grain, hay and livestock. They may still house the occasional litter of raccoons and mouse-killing black and milk snakes, but one apparition is far less common among the rafters.

Helpful hunter

The monkey-faced specter that once looked down with curiosity before vanishing deep into the shadows or disappearing through a haymow window to escape into the twilight is now a rarity. This co-existing neighbor’s job on the family plot was to kill grain-robbing rodents, meadow voles being a favorite.

Far more efficient than the lazy barn cats who spent their time in the milking parlor, its family could eat more than 1,000 of their favorite fuzzy sausages a year with some estimates tripling that number. This is Ohio’s native barn owl.

Those old barns failed to maintain their value in a changing farm economy, and that has contributed to the housing shortage for this valuable owl. A reduction of livestock also diminished the need for hay fields and pastures. The barn owl, the friendly ghost of the rafters, was vanishing and its existence threatened, but hope continues.

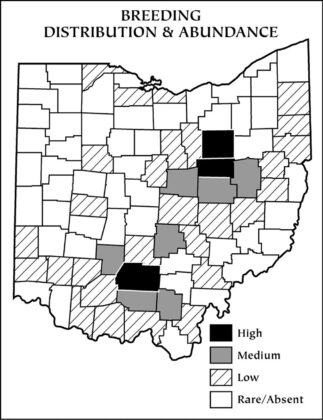

The barn owl’s prime hunting grounds consist of wet meadows, hay and lightly-grazed pastures, especially in counties along the glacial border of Ohio. Nests are typically located near these areas. Besides the old barns, they’ll use abandoned buildings, silos, chimneys, as well as hollow trees and specialized nesting boxes.

Advocate

Some of the early information about Ohio’s barn owl populations was collected by Laurel Van Camp during his “off” hours from his regular job — a job that was intrinsically woven into his very being. Laurel was the Division of Wildlife’s Ottawa County Game Protector – now known as a Wildlife Officer or universally as a game warden. He was also a man who considered himself a full-time naturalist.

He was an advocate for protecting all birds of prey, while many, including some of his peers, advocated shooting them on sight. His studies and those of other biologists would prove this as short-sighted — a poorly researched solution to dipping game bird populations.

Van Camp witnessed declines in many birds that were not included in the hunting seasons. He quickly identified the problem as the diminishing habitat due to the rapidly changing agricultural economy and the increase in the efficiency of farm drainage and harvesting.

Along with the likes of Rachel Carson, he recognized the negative impacts of some of the pesticides that were being used and the destructiveness of tolerated pollution. He was a voice for Ohio’s birds and wildlife and became a recognized authority on the subject.

Born in Wood County in 1904, Van Camp passed away in 1997. Thankfully, he lived to see the outlawing of killing raptors, the banning of pesticides like DDT, the birth of the EPA and the tightening of pollution regulations and the purchases, expansions and protection of the Lake Erie marshes he loved.

Thanks to Laurel Van Camp and other far-sighted wildlife biologists and naturalists, many species were saved from a very uncertain future. Unfortunately, habitat issues still exist.

Conservation plan

In 2013, Ohio’s Division of Wildlife’s barn owl conservation plan was updated to set population objectives and establish a monitoring protocol to assess their population size and distribution. A goal was established at a baseline of 100 active nests sustained for at least three years. These nests would be monitored by division personnel and volunteers.

Most of the monitored nest sites are found distributed within select townships in 17 counties, which offer the best habitat structure. These include Ashland, Belmont, Brown, Fayette, Franklin, Guernsey, Holmes, Jackson, Knox, Morgan, Muskingum, Noble, Perry, Richland, Scioto, Tuscarawas and Wayne.

Through the winter of 2019, the division installed nesting boxes in 122 of 130 identified targeted townships, many of which are maintained by private landowners and volunteers. That year, division staff and partners found evidence of seven nests from the 2018 season. Volunteers added another 54 nests, raising the total for the season to 61, still below the targeted goal. Since the barn owl’s recorded population remains below the established objective, it will remain as one of Ohio’s threatened species.

Reporting barn owls helps to estimate how many exist in Ohio. This information benefits conservation efforts by tracking where and how they live. They are easily identified by their white, heart-shaped face, large black eyes and golden-brown and gray back. Finding pellets is another indication that barn owls may be living nearby. Pellets are regurgitated bones and fur of their food.

If you believe one is living nearby, you can report the sighting online at wildlife.ohiodnr.gov by following the “Report Wildlife Sightings” tab, by calling the division at 1-800-WILDLIFE or you can use the Hunt Fish Ohio App, which is available free. It can be found on your smartphone App/Play store.

If you want to add a barn owl nesting box to your own property, visit the Barn Owl Box Company at www.barnowlbox.com for some great ideas. If you can cut a few boards, you might choose to make your own. Visit homegrail.com/diy-barn-owl-box-plans/ for 11 solid choices.

We owe the men and women like Laurel Van Camp our thanks for the barn owl and many other species’ continued presence. It’s their foresight that help focus the visions of today’s wildlife protectors.

“I am only one, but I am one. I cannot do everything, but I can do something. And I will not let what I cannot do interfere with what I can do. And by the grace of God, I will.”

— Edward Everett Hale