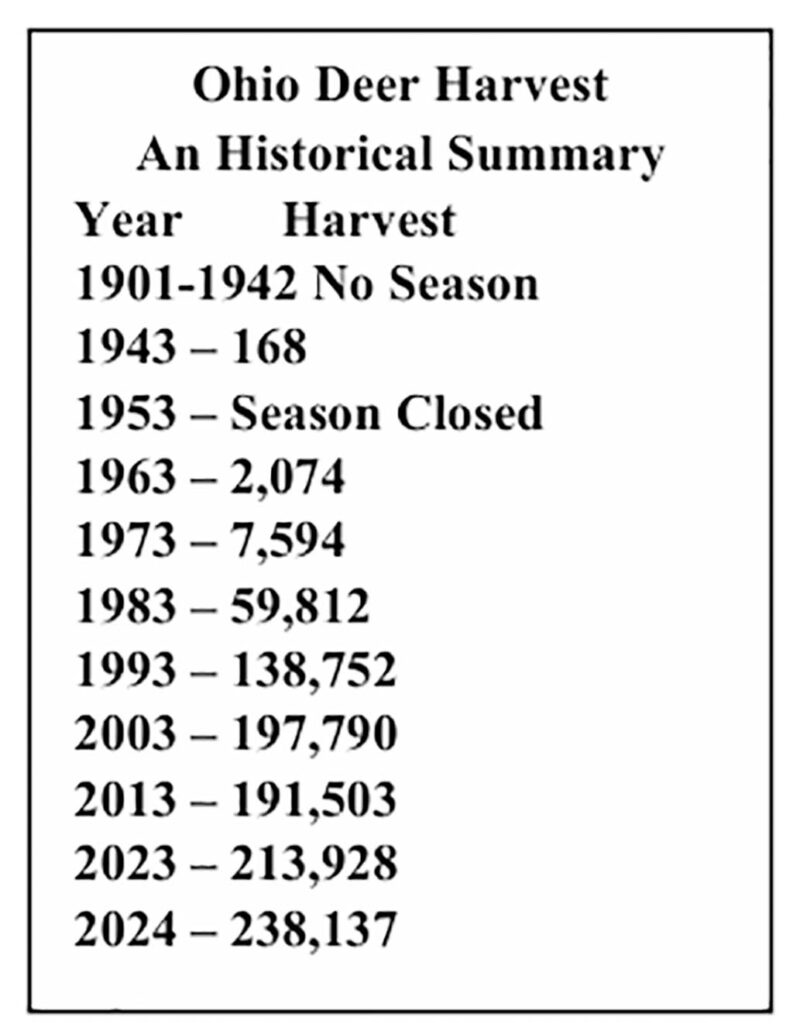

Since I started working for the Division of Wildlife in 1983, Ohio’s deer hunting seasons have changed dramatically. It might be interesting to take a look at those shifts from a warden’s viewpoint. This isn’t a historical record in which I’ll pull out all the data, just some perspective.

During my first years patrolling the back roads, hunters could harvest deer using smoothbore shotguns, archery equipment — including the then recently added crossbows — and single-shot, muzzle-loading long guns. The limit was one deer per year. Bucks with antlers three inches or taller were legal game, but antlerless deer were off-limits except for archers.

A new permit was introduced in the early 1980s, which allowed antlerless deer to be taken during gun season. These permits were county-specific and were randomly drawn from applications. These allowed a hunter to kill an antlerless deer in the county it was assigned, and was often called a doe permit by sportsmen. There was discontent among hunters and landowners about their issuance. Opposed to killing does, petitions were sent to division offices threatening to disallow deer hunting on their farms. Others applied for permits, then destroyed them.

During this time, few issues arose during bow seasons — other than the occasional “hunting without permission complaint” (HWOP). There were always some who cheated by shooting deer with a firearm, then claimed it as a bow kill. Others purchased tags after the fact, had a friend or family member tag a deer illegally or weren’t concerned about tagging or game-check laws at all. Some got caught, some didn’t. I discovered some through experience, others by tips and a few by dumb luck. Bow harvests were far less significant compared to gun season totals.

The gun season, which began the Monday following Thanksgiving, lasted one week — there was still no Sunday hunting. This was a busy time with calls being dispatched from county sheriffs’ departments and division dispatchers. Days often began at dawn and stretched well into the night, with aircraft and spotlighting projects scheduled during the week. It was a time of running from call to call and contacting as many hunters as possible. It could also be dangerous. Poachers were interspersed among honest contacts, and officers seldom knew what type of person or situation they were approaching. There was also the risk of poor gun handling skills, accidental discharges, and the rare hunter-involved injury accident.

HWOP was the primary complaint. Of course, there were tricksters who would have others tag their deer or would purchase licenses after the kill. The antlerless permits were something that always drew officers’ attention. Most sportsmen and women were absolutely honest in their use, but a few played those permits like a riverboat gambler. More than a few tried to get across county lines in the hopes of changing a dead deer’s residency.

Group play

Issues developed around some of the large hunting groups that had manifested themselves in the western half of the state. My own thoughts are that this methodology of “group hunting” grew from the tradition of the old fox hunting clubs that were so popular from the 1930s through the late 1970s, a time of scant deer populations. Without real deer hunting experience, they used an already familiar hunting technique.

As always, most played by the rules, but a few groups didn’t bother reading the book. “Group tagging,” trespassing, unsafe gun handling, loaded firearms in — and shooting from — vehicles, untagged and unchecked deer and shooting from the road all became issues. These antics caused safety concerns and resulted in a great deal of land being shut down to deer hunting. A lot of the game protector’s (now called wildlife officers) time was spent answering complaints and working on projects directed at curbing that illegal activity. We wanted landowners to know that we had their back — and that we were there to protect the integrity of honest sportsmen and women. I’m not sure some of the scofflaws felt that way.

Hunting tech evolves

The muzzle-loading seasons were something of a hybrid of the bow and gun seasons. Many hunters were no longer in the field because they’d “tagged out.” The majority were honest, though there were a few trying to fill “family” tags or had become too desperate to harvest a deer. Sometimes, during those far more frigid hunting conditions and competing football games, finding a hunter could be difficult, while at others, it could become amazingly busy.

Handguns and rifled-barreled shotguns were added to deer hunters’ options in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s. Inline muzzle-loading rifles were also given the okay. A few officers expressed apprehension about handgun hunting, although none of those worries materialized. Actually, very few hunters chose that option. Inline muzzleloading rifles became very popular and have now supplanted the once far more common percussion-capped and flintlock rifles. The inline front-stuffers benefited from improved bullet designs, easy scoping and familiar handling qualities, making them very effective at harvesting venison. Rifled shotguns and their newly developed sabot ammunition also proved increasingly effective deer-droppers. As a wildlife officer, I began to see very few smooth-bore shotguns that had been the norm just a few years prior.

During the mid-1990s, the deer population had continued to grow, and harvest numbers were setting records. Landowners and hunters now accepted the idea of harvesting antlerless deer as part of sound herd management. The antlerless tags yielded to “either-or” choices, and additional deer harvests were being permitted. Still, only one buck was allowed.

Archery interest grows

Compound bow and crossbow technology were advancing quickly. Hunters found that the long and unhurried bow season offered relaxing and solitary opportunities. Permission to hunt was also easier to obtain. Additionally, the interest in archery was growing. Dedicated bowhunting clubs and projects like the “Archery in the Schools Program” were certainly influencing aspiring hunters. The Division of Wildlife began adding archery ranges around the state, including at many district offices. This rising archery interest was beginning to lighten the number of hunters participating during Ohio’s traditional gun seasons.

In the 2000s, the deer herd had continued to increase. A large number of Ohio hunters now focused on deer as their primary quarry. Straight-walled cartridge rifles were approved by the Ohio Wildlife Council in 2014. Easier to load and shoot, the division hoped that they might help recruit or repatriate hunters who were skipping the gun season.

With rising deer numbers, crop damage complaints helped open more land to hunters. In-season harvest permits were available to farmers, as well as closed-season kill permits. Parks and urbanized areas began offering controlled hunts to manage local whitetail numbers and control browsing damage. Bowhunters seemed to especially benefit from these situations.

Today, deer — once looked upon as something of a sacred cow — are now seen as the renewable resource that they are. The archery harvest began surpassing the gun season’s, something once thought impossible — or at least improbable. Increasing deer numbers, increasing opportunities and increasing interest in archery all played their role.

Health issues

While the Ohio deer herd has long been noted for its exceptional health, and because Ohio whitetail bucks were among the nation’s finest, some dark clouds were on the horizon. These came in the form of two zoonotic diseases. The first to hit Ohio was the infamous CWD (chronic wasting disease). Closely associated with “mad cow” disease, which first hit European livestock during the mid-1980s. CWD is a neurological disease affecting the brain and central nervous system of an infected animal.

The other black cloud for Ohio whitetail populations came in an actual black cloud of small midges (very small flies with a bite). EHD (epizootic hemorrhagic disease) is raising concerns in the state, especially in the southern counties. It’s caused by an infected midge’s bite and is likely to be fatal within about three days. It’s also one of the more common diseases inflicting whitetails around the country.

Back to better news

Ohio’s whitetail limits are quite different from the one deer per year of the 1970s. Today’s deer hunters may take up to six deer per license year, of which only one may be an antlered buck. While the state’s majority of its 88 counties have a three deer limit, there are five counties (Cuyahoga, Franklin, Hamilton, Lucas and Summit) that offer a four deer bag limit and seven (Defiance, Hocking, Jackson, Lawrence, Paulding, Vinton and Warren) limited to just two. Ohio’s six-deer bag limit requires you to hunt in more than one county to fill six tags. The statewide archery season opens Sept. 27.

Ohio’s Wildlife Officers are still busy, but unlike those “old days” of my young career, the deer hunting workload is spread over months. Of course, the cheaters are still out there, and officers need to work differently to catch them. With archery’s growth in popularity and landowner acceptance, lawbreakers are now found sneaking into their numbers.

Changes for the officers have come in the form of technology. In-car computers, improved communications, updated surveillance gear and techniques and computerized harvest records and licensing programs have all helped sharpen the warden’s pencil. The division also has a dedicated cadre of tech-savvy investigators and covert operatives to help go after the real problems.

With all of that, the Division of Wildlife still needs your help. If you have any information or suspicions regarding wildlife violations, call 1-800-POACHER (1-800-762-2437) or report it online at wildohio.gov. You can remain anonymous.

You can help Ohio’s wildlife by reporting suspected EHD or CWD and by reporting key wildlife sightings. To make a report, visit www.ohiodnr.gov/discover-and-learn/safety-conservation/stewardship-citizen-science/wildlife-reporting-system/wildlife-reporting. While that web address is a long one, you can also download the free HuntFish OH mobile app for Android and iOS. It offers the quickest access, and it can be carried in your pocket.

“All the sounds of this valley run together into one great echo, a song that is sung by all the spirits of this valley. Only a hunter hears it.”

— Chaim Potok