SALEM, Ohio — A bloodthirsty arachnid is lurking in Ohio pastures, and Ohio State University is at the forefront of monitoring its movements.

This arachnid is the Asian longhorned tick, and like many other ticks, it can transmit diseases that have long-lasting effects.

That’s why this creepy-crawly is the focus of the university’s recently opened Buckeye Tick Test, a new pathogen testing service that identifies ticks with disease. OSU is also working directly with producers on projects to learn more about the Asian longhorned tick’s life cycle.

“Right now, (the research is) mostly from Rutgers in New Jersey,” said Tim McDermott, an agriculture and natural resources assistant professor at OSU Extension Franklin County. “If we can get some better data here, then that’s going to help us have Ohio-specific (information).”

OSU and Asian longhorned ticks

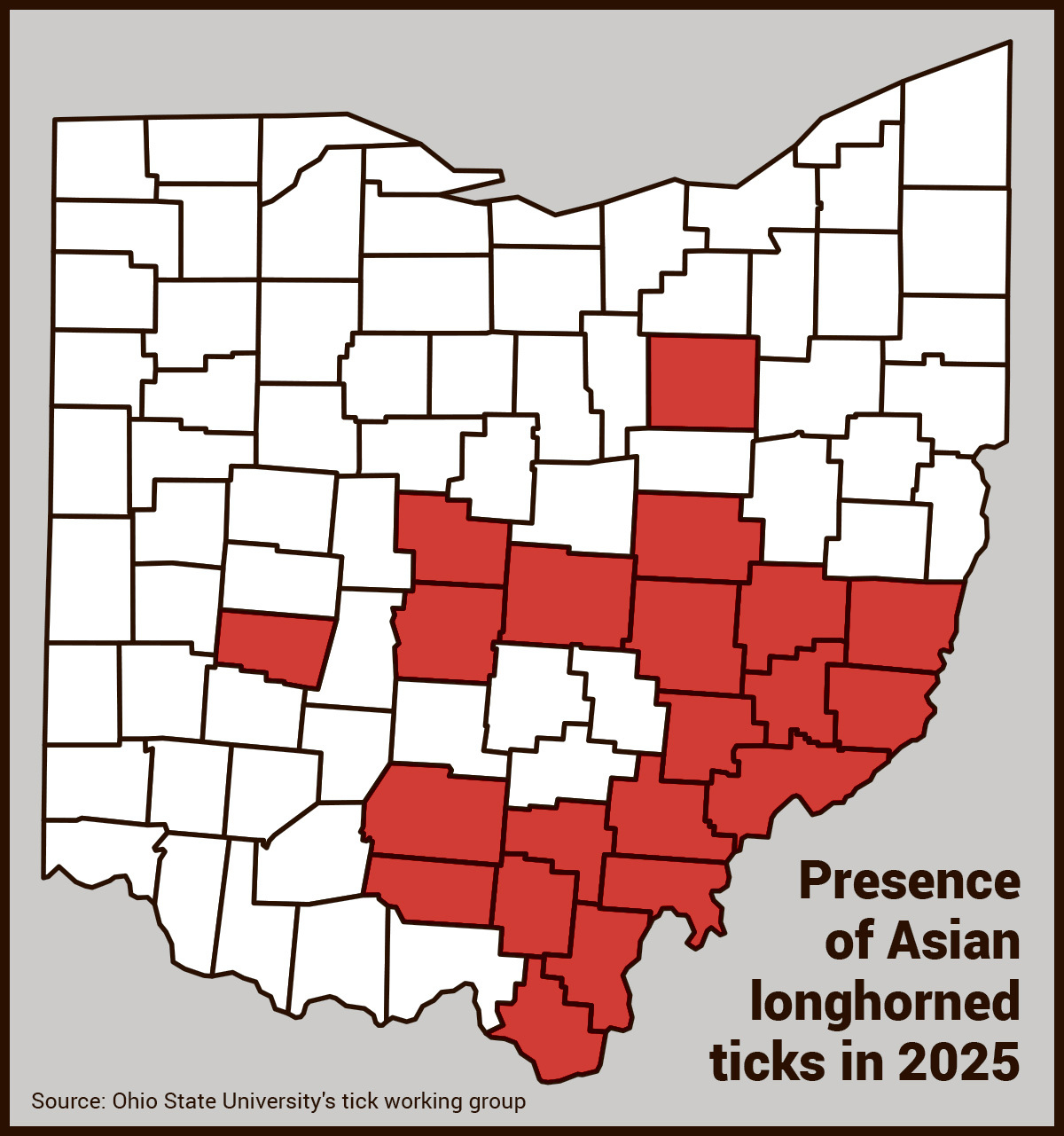

The Asian longhorned tick was first found in Ohio in 2020 in Gallia County. The following year, two more counties had the tick, said McDermott.

Since then, the tick has steadily spread; today, it is present in 21 counties, McDermott said, including Athens, Belmont, Clark, Coshocton, Delaware, Franklin, Gallia, Guernsey, Jackson, Lawrence, Licking, Meigs, Monroe, Morgan, Muskingum, Noble, Pike, Ross, Vinton, Washington and Wayne counties.

The biggest concern regarding Asian longhorned ticks is their ability to spread Theileria Orientalis, a pathogen transmitted to animals, mostly cattle, that they bite.

Cattle that contract theileriosis may develop high heart and respiratory rates, a fever, jaundice or stop eating. Female cattle might have stillbirths or abortions. The disease can be fatal.

According to McDermott, Asian longhorned ticks can also kill cattle by exsanguination — meaning they suck all the blood out of the animal — if enough are present.

This was the case for an Ohio farmer in Monroe County in 2021, when Ohio State University researchers received a call that three of his 18 cattle had died after being heavily infested with ticks.

McDermott estimates, however, that the mortality rate of cattle with the disease is around 5%. Theileria is present in at least 13 counties, he said. There is no treatment for theileriosis, so testing ticks found on cattle is crucial.

Buckeye Tick Test

That’s part of the reason why Ohio State founded its Buckeye Tick Test service earlier this year. The testing service takes place in OSU’s College of Veterinary Medicine lab, with the goal of identifying species of ticks and what pathogens they may carry.

Anyone, even those living outside of Ohio, can submit a tick for testing. This information can then be shared with physicians or veterinarians, McDermott said.

“This will allow us to have better samples sent to us … and now we’ll have better data on what ticks are where and what diseases they’re carrying,” he said.

This testing also helps the lab identify new counties with the Asian longhorned tick. OSU wants to work with extension educators in new counties to develop educational programming that assists cattle producers.

McDermott adds that farmers should get testing done on ticks, as they could be compensated for cattle losses through the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Livestock Indemnity Program if they die from theileriosis. Farmers need a positive theileriosis test to receive compensation.

Other research

Ohio State is pursuing other avenues of research to learn more about the Asian longhorned tick, including on its research farm in Jackson County, Ohio. There, the university conducts routine Asian longhorned tick surveillance. According to McDermott, this farm was one of the first places the tick was found in Ohio in 2021, and every year, ticks are found on the farm.

Cattle farmers in the state also participate in on-farm research with OSU. This consists of checking the animals for ticks and tick dragging through pastures to identify the number of Asian longhorned ticks on the farm.

Farmers interested in on-farm research should reach out to their local Ohio State University Extension educators. For more information, visit https://idi.osu.edu/idi-gems/buckeye-tick-test.

A panel of cattlemen is also participating in OSU research to see how the Asian longhorned tick survives in stored forages. McDermott says the goal of the projects is to “see about modifying habitat and obtaining data on the phenology of the life cycles of them here.”

What you can do?

Although producers can’t prevent theileriosis from occurring, they can take steps to minimize ticks on the farm. Farmers can mow a buffer strip around the perimeter of pastures to reduce tick populations.

Pesticides specifically for ticks can also be applied to cattle and pastures; however, McDermott notes that for these pesticides to be effective on pastures, it must come in direct contact with ticks. He adds that farmers should read the label before spraying any pesticides.

Above all else, McDermott recommends scouting animals often and having a relationship with a veterinarian or someone who can conduct tick testing.

“It’s really more of an integrated pest management approach. There’s not one silver bullet,” McDermott said. “There’s some things you can do with pasture, and then there’s some things you can do with animals, and then scouting is a big thing.”

(Liz Partsch can be reached at epartsch@farmanddairy.com or 330-337-3419.)