It’s trendy to call diseases — some of them extremely serious — by their initials rather than their full names, so perhaps it’s appropriate that the spotted lanternfly is now abbreviated to SLF. And the serious damage this invasive species could cause to Ohio’s grape, hops and orchard industries, for starters, has brought agencies together to fight its spread.

Targeting Northeast Ohio

In more than 20 counties in Northeast Ohio, in a line from Interstate 70 north to Lake Erie and from Muskingum County east to Pennsylvania, you may see black traps shaped like bishops’ hats that have been deployed along interstates, railroad tracks and other transportation corridors.

In addition, you may see billboards, posters and even videos about spotted lanternfly at truck stops and rest stops. You may also see those posters, plus SLF “ID cards,” if you visit your favorite wineries, breweries, nurseries or orchards in those counties. The wallet-sized cards show how to identify spotted lanternfly in all its life stages. They also have a barcode that can be scanned for more information.

“We’ve identified Northeast Ohio as the concentration point for this effort because of the abundance of railroads and interstates and its proximity to Pennsylvania,’ said David Adkins, Agricultural Inspection Manager for the Ohio Department of Agriculture (ODA), who also works in the state’s Plant Pest Control Program.

The spotted lanternfly, an invasive species from Asia, was first discovered in Pennsylvania, just northwest of Philadelphia, in 2014. It has since spread to seven other states, including West Virginia. A total of 26 Pennsylvania counties are under quarantine for SLF, including Beaver and Allegheny counties that border Mahoning and Columbiana counties in Ohio.

Working together

The ODA is working with the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS), plus the Ohio Department of Natural Resources and The Ohio State University Extension in efforts to detect SLF “hitchhikers” and exterminate them before they can create an infestation. The Cleveland Metroparks, as well as Master Gardeners in many counties, are helping with early detection, as well as educating the public.

“We’re trying to get as many boots on the ground as possible,” Adkins said. That includes boots that belong to owners of vineyards, orchards, and nurseries and hop growers.

The spotted lanternfly’s preferred host plant is the tree of heaven, also an invasive species, Brought from China in the late 1700s, it flourishes along railroad tracks, roads and other places where there’s been construction or disturbance. Part of the early detection effort is monitoring these trees for signs of SLF.

Second-favorite foods

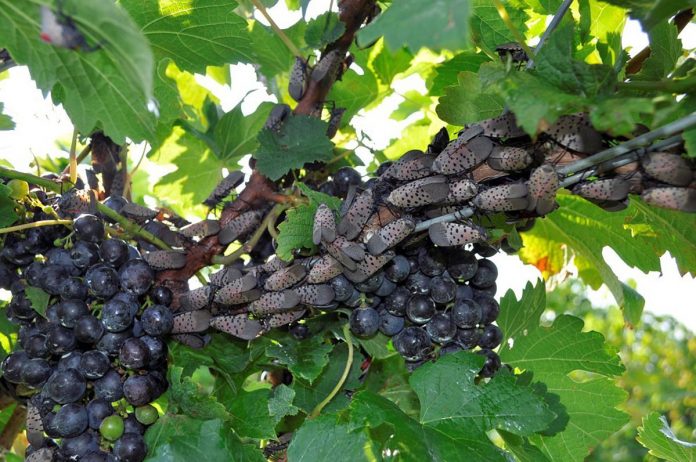

It turns out, however, that grapevines, fruit trees and hops — along with hardwoods and perennials — are among the spotted lanternfly’s second-favorite places to dine.

“These are the crops that are among the first that could be affected” by a serious infestation, Adkins said.

Thomas deHaas, Agriculture and Natural Resources Educator with the OSU Extension in Lake County, has been working with owners of nurseries and orchards, plus the many vineyards and wineries in the Grand River valley, to get information about spotted lanternfly into the hands of their customers.

The invasive insects are phloem feeders, he explained. They penetrate the bark or surface of the tree or vine and feed on the sugars that the plant produces in the leaves. That means the sugars don’t make it down to the roots, which can deteriorate and weaken the plant, including its ability to resist cold.

In the case of grapevines, “if they’re only cold hardy to five below and it gets to 15 below, the vines can die,” he said.

Honeydew

Another source of damage is the massive amount of sugary poop they produce, euphemistically called honeydew. It covers the bark, leaves, fruit — everything — which leads to a sooty fungus or mold that can also weaken the plant, even kill it, deHaas said.

To help fight the SLF wars, he has enlisted the more than 40 Master Gardeners in Lake County. Each has had more than 60 hours of training through the extension. They do a lot of outreach and education, such as talking to garden clubs, deHaas said.

That’s why, as soon as COVID restrictions end, he hopes to get them doing outreach and education about spotted lanternfly. Also, each will “adopt” a tree of heaven and monitor it for signs of invasion, he said.

Specialist

Amy Stone is Agriculture and Natural Resources Educator for the OSU Extension in Lucas County, at the other end of the North Shore. She has been on the front lines of the invasive species battle in Ohio since a gypsy moth infestation in her county in the mid-1990s.

In 2003, she was the first to find an emerald ash borer infestation in the state, then headed up an EAB project in Ohio with support from the USDA and Forest Service for 10 years.

With such credentials, it’s not surprising that she was a source of information for an article about spotted lanternfly in this month’s issue of Smithsonian Magazine. While she was quoted as saying that no SLF infestation has been found in Ohio, she says there have been incidents of single, adult hitchhikers.

One was found on the car of a man who’d been on vacation in Pennsylvania, another on a fuel pump at a truck at a truck stop in Zanesville. A third was nabbed inside the cab of a truck that was delivering materials to Lorain County. In all cases, the hitchhikers were positively identified and killed.

“Right now the various agencies are following up on the suspects to make sure they were the only ones,” Stone said. And that they didn’t lay eggs, if they were female. While they might lay somewhere on the vehicle, like the back side of a hubcap, they could also lay eggs “on any flat surface, like a tree or a stone, which can be hard to find,” she said.

Spotted lanternfly females lay in masses of between 30 and 50 eggs now, in the fall. They cover them with a mud-like material that protects them until they hatch in the spring, beginning in April and continuing through May and June. When they hatch, they can cause a new infestation, Stone said.

If that happens at someone’s home, as it sometimes does in Pennsylvania, the trees, yard, even children’s toys, can become covered with hundreds, even thousands of insects, and the icky honeydew they produce. “It’s really a mess, and it prevents homeowners from enjoying their landscape,” Stone said.

Report sightings

That’s why it’s crucial to report possible SLF sightings so the insects can be positively identified and dealt with, she said. Calling your local Extension office or the Ohio Department of Agriculture is a good start. There’s also an app for that.

The Great Lakes Early Detection Network app can be used to report spotted lanternfly or egg masses, or finding a tree of heaven. The app then records the GPS coordinates so the area can continue to be monitored. It can also be used to report other invasive species of insects, plants and animals.

Stone, deHaas and Adkins are all part of the growing task force that is doing its darndest to prevent a spotted lanternfly invasion of their state. But they all agree on one thing: “It’s going to come to Ohio, it’s just a matter of when,” deHaas said. “When it does, we have to do our best to identify and contain it.”

It’s nice to educate what spotted lantern fly’s are, butthere is little information on how to kill them besides squash them

The problem is, if you run out & buy some killer pesticide like Round-up, it can kill you too.