When writing columns about Ohio’s wildlife, I rarely stray from the animals that you’re most likely to find in the state’s woods and waters or stories about hunters and anglers. Okay, I do admit to writing about bull sharks in Lake Erie, but in my defense, that was on April Fool’s Day. So, believe me when I say that I have never had any intention of penning a story about armadillos — that is, until two were found in Ohio.

Armadillos

First of all, let’s take a look at this unique armored animal. A relative of anteaters and sloths, the armadillo’s name is derived from Spanish and means “little armored one,” and the Aztecs referred to them as the “turtle rabbit.” To wildlife biologists, the little tank is known as Dasypus novemcinctus.

According to those who study ancient fossil records, all of the armadillo species seemed to have evolved in South America. During the eons, land masses shifted and a continental bridge formed that linked South, Central and North America. A few of those armadillo species decided to head north.

It was the nine-banded armadillo that moved furthest and is the one found in the south-central states. Whoever named this critter in a half-shell must have been averaging out the number of bands on its back. If you decide to do a count yourself, you’ll find that the nine-band can have as few as seven and as many as eleven circling its upper body. Today, armadillos are a regular sight in Texas, and one that I’ve run into (actually, swerved around) several times.

When threatened, some members of the armadillo family may roll up in a protective ball, offering only a bite of scaly armor, but the nine-banded variety isn’t one of them — he’s a jumper. When startled or attacked, the nine-band will leap into the air in an attempt to repay that scare with a scare. I guess an odd-looking, two-and-a-half-foot, 12-pound leaping what’s-it would make me hesitate. That’s when it’s likely to scurry away — looking more like a panicking sowbug (pillbug). A peaceful sort that is plagued by poor eyesight, it often stands up on its hind legs to listen and to test the air if it senses danger, which usually comes from bobcats, coyotes, raccoons, some raptors, humans and road traffic. While nine-banded armadillos aren’t aggressive toward people or other wildlife, a frightened armadillo may nip or scratch if you pick it up.

While escaping, don’t be surprised if it jumps into a creek or pond, either. While they look like they would sink like a rock, nine-banded armadillos are really pretty good swimmers. They’ll actually swallow gulps of air to increase their buoyancy. As for sinking like a rock, they’ll sometimes choose that route, too. They’ll forego air-gulping and wait to hit bottom and then start walking. They can hold their breath for up to six minutes or a bit more before having to surface.

A common site in the Lone Star State as well as a few others, Texas armadillos are not considered a game animal. It’s not off-limits to hunters or to those having issues with the animal. Their tendency to burrow and their propensity to inhabit some urban settings raise similar issues that Ohioans experience with the sometimes-troublesome woodchucks. They dig underground dens, and when they’re looking for food, armadillos may dig numerous 1- to 3-inch holes in golf courses, lawns, flowerbeds and gardens.

Another downside of the interesting nine-banded armadillo is that it’s the only animal besides humans to host the leprosy bacillus. Before you panic, Laura Clark reports through Smithsonian Magazine that “Though Hansen’s disease, as it is clinically known, annually affects 250,000 people worldwide, it only infects about 150 to 250 Americans. Even more reassuring: Up to 95% of the population is genetically unsusceptible to contracting it… And as for armadillos, the risk of transmission to humans is low … most people in the U.S. who come down with the chronic bacterial disease get it from other people while traveling outside the country.”

If you see one of these nocturnal creatures rooting around like an armored piglet, they’re just looking for lunch. They eat insects, grubs, worms, snails, spiders, scorpions, beetles and wasps. They’ll sometimes eat small frogs, lizards or eggs and will occasionally munch on fruits, berries and seeds.

Back to Ohio’s sightings

Yes, it’s true. Two nine-banded armadillos have been found in the Buckeye State. According to the Ohio Department of Natural Resources Division of Wildlife, on May 11, 2021, one showed up near Mansfield at the State Route 13 and Interstate 71 off-ramp. The other was found on June 21, 2021, at the exit ramp from Interstate 71 to State Route 95 in Morrow County. To put it in southern forensic terms, both were DRT, dead right there, having been apparently struck by traffic.

The division believes that these two were not residing in the state, but had hitchhiked their way into Ohio by accident. There was a rumor of a live specimen possibly being sighted near Columbus on Olentangy River Road, though it couldn’t be relocated for positive identification. I think the Division of Wildlife’s assessment is correct. My reasoning is that if we are seeing an army of armadillos invading the state, it would start in the southern counties and not just suddenly flair up in mid-state. Surely, someone would have noticed. But really, what are the odds of ever seeing armadillos calling Ohio home?

Apparently, better than we think. Kentucky has a stable population of armadillos roaming around the state. According to the Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife, “Reports of nine-banded armadillos in Kentucky started in the mid-1980s. Throughout the mid-1980s and 1990s, the department received only occasional reports of armadillos, but by the early 2000s they had become fairly common in counties as far east as Land Between the Lakes; expanding to the north and east from Mississippi, Alabama and Tennessee… The terrain and cold weather of eastern Kentucky may have functioned as an ecological barrier to their migration in the past, but this may change in the coming years. Thus, it is possible that soon we may see armadillos in every county in Kentucky.”

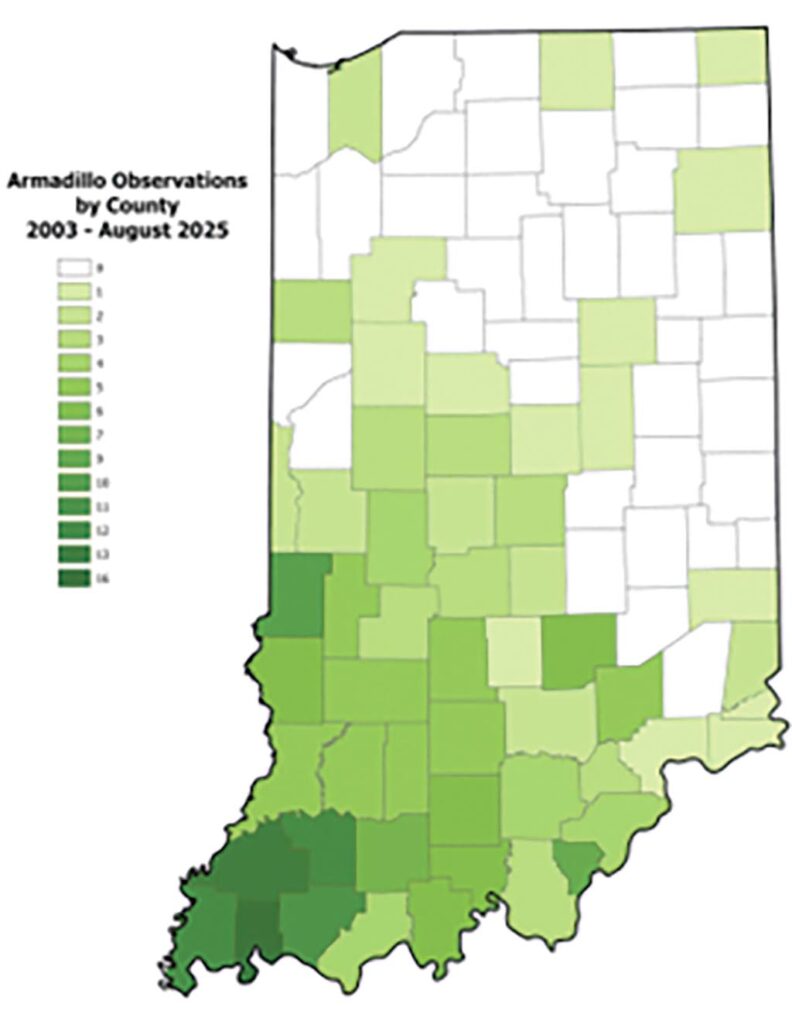

Our western neighbor, Indiana, also has a bunch of nine-banded armadillos who have declared themselves Hoosiers. According to information from the Indiana Department of Natural Resources, during the early 2000s, reports of armadillo sightings on Indiana’s roadways were first noted in the southwestern portion of the state. Recent observations of live and roadkill armadillos indicate this species can be found year-round across the southern half of Indiana, with reports of armadillos being received as far north as Porter County. Indiana laws protect armadillos, and they cannot be killed, trapped or captured unless it’s causing substantial damage to property.

How far will the nine-banded armadillo travel north? The animal was first documented in Texas by the mid-1800s, then eastward to Florida by the early 1900s. They then began expanding northward. Their expansion will be slowed and eventually stopped as they encounter winters with extended periods of sub-freezing temperatures. Their sparse fur, limited body fat and generally low body temperature make armadillos susceptible to hypothermia. Limited winter forage could also cause starvation during winter months. The nine-banded armadillo will eventually meet its atmospherically-held limits, but for right now, they’re still exploring new homeland opportunities.

Kind of looks like one of these days, we’re going to get some company.

“The armadillo wears its armor, not to fight, but to endure.”

— Anonymous