Several years ago, I was talking turkey hunting with a friend when he mentioned that he’d reaped a nice gobbler in Seneca County, Ohio. I’d thought I’d misheard him, and the dumb expression on my face must have given it away. “R-E-A-P-E-D, reaped,” he spelled. “You know what it is… right?” I felt like I was failing a fourth-grade spelling bee. It seemed apparent that his confidence in his game warden buddy was a bit shaken.

There is no shame in ignorance, only in the denial of its existence. As if on cue, he then did what every successful hunter has done since the world’s first hunter returned to the campfire. He took most of two hours to describe what had happened inside of 15 minutes. When he was done explaining how he’d arrived at the turkey woods at zero-dark-thirty, everything about the camo patterns he’d chosen, his boots, gun, shells, spilled coffee, the deer he saw, the owls hooting, the bothersome squirrels surrounding him, how he almost forgot to turn off his phone — I think you’re getting the picture. That preamble dragged on for the first hour before he finally got to the hour-long reaping part. Having begun to doze off, I almost missed the explanation.

The reaping

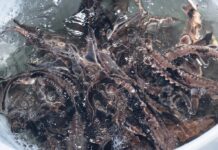

It seems he’d taken a previously bagged gobbler’s tail fan and belly-crawled his way toward a strutting Tom as he danced the fan in front of his own face, disguising his approach. As he crabbed along, he used a diaphragm call to give a cluck, a low gobble and other turkey noises on his way. When he got close enough, he gave the big bird a load of number six shot and took it home to the deep fryer. Simply put, that’s all that reaping ends up being, hiding behind some turkey parts or a decoy and sneaking up close enough to blast or arrow a longbeard. It’s also led to “fanning” which employs turkey wings.

This was news to me, so new that I knew nothing about it. It sounded like an intriguing hunt, though I felt a little unsettled with the idea of being camo-ed up and hiding behind a turkey tail in a forest that might have hunters just itching for a shot. I just don’t care to become a government statistic.

Apparently, there’s quite a discord in the gobbler nation about using reaping as a harvest method. Detractors sometimes call it reapercide, arguing that it’s a foul way to fool fowl, going so far as to claiming that it takes away from the moral code of fair chase. These folks like to point out declining turkey numbers that have occurred over much of the turkey’s world and what they see as an unfair harvest advantage. They also emphasize what I instinctively saw as a possible problem: the increased risk of a hunting accident.

Those who practice the technique claim that it helps to get birds that are stuck out in open areas such as the patchwork of farms and trees in much of Ohio. They say it’s also effective on “stuck” birds — those that just refuse to come close enough to the call. They’ll explain that reaping can be effective in woodlands, where birds are looking for their own kind moving around. Since gobblers willingly defend their harem, they may lose caution when they see a strange bird approaching and begin strutting around with an attitude. It must be quite a surprise when they find out the invading gobbler showed up with a shotgun.

Like any efficient predator, human hunters have adapted their techniques to be successful. Proponents are quick to point out that reaping is not that much different than using decoys. The actual change is from using the traditional ambush tactics using calls and (sometimes) decoys placed away from the hunter to using decoying tactics when stalking the gobbler using reaping and fanning techniques.

Reaping has become enough of a controversy that some states have declared it illegal. A recent survey of hunting agency rules turned up that Alabama, Michigan, New Hampshire, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and within wildlife areas found in South Carolina and Tennessee have enacted a ban on stalking, fanning and reaping. Other states offer special precautionary warnings about the safety of using the technique. Currently, Ohio doesn’t appear to be entertaining any regulations concerning the practice — of course, that can change. Always review the hunting regulations before heading to the field.

I really have no issue with either of the arguments that the two factions offer. Tradition has always held a strong influence on much of sport hunting. It’s hard to change, but change does come. At one time, it was thought ethically corrupt to shoot doe deer in the state, while today it’s not only common, but is encouraged. Hunting with muzzle-loading rifles was once exemplified by replica Hawkins and long rifles, now inline designs have taken over. Those are hard things for traditional attitudes to accept — it takes time. Could reaping and fanning be in the same category?

While I doubt that the method is ethically wrong or that it’s become a widespread threat to turkey populations, those are just my unscientific opinions. What I can see is the potential risk. The shooter will ultimately be to blame for taking aim at an unverified target, but there are no winners in a hunting accident. The Ohio Division of Wildlife correctly calls them “hunting incidents,” and they’re the ones that investigate these mishaps and are the expert witnesses in court when a shooter is charged.

My verdict?

If it’s legal where you hunt and you can accept the risks, go ahead and reap away. Myself, I think I’ll take a pass. I hunt my own ground where I should be the only turkey hunter, but that doesn’t mean that someone might not sneak in. For me, the risk isn’t worth a turkey dinner.

If you do decide that you’d like to give it a try, I’ve heard that it’s quite an exciting way to bag a bird. I would just discourage you from going to public hunting grounds in heavily wooded areas. You may be surrounded by turkeys of all ages and experience, but there’s also a good chance that there will be turkey hunters falling into those same categories, too — anxious to shoot their first bird. I especially wouldn’t use a gobble call while hiding behind any turkey decoy!

Have a great season and, most of all, be safe!

“You don’t need to know the whole alphabet of Safety. The a, b, c of it will save you if you follow it: Always Be Careful.”

– Colorado School of Mines